L'Académie Française: Making Sure Learning French Is Never Too Easy

The birthplace of your favorite rules and regulations!

by Brian Alcamo

France is governed by the French government, but French is governed by L’Academie Française (in French, it is spelled L’Academie francaise, the French don’t seem to be big fans of titles with too many capital letters). This centuries-old body is the reason why French learners (and native speakers, too) spend countless hours trying to remember painstaking rules such as having to make a past participle agree in gender and number with a direct object if said direct object is placed before the verb. For example:

Est-ce que tu as acheté le livre ? Oui, je l’ai acheté.

Est-ce que tu as acheté les fleurs ? Oui, je les ai achetées.

This particular rule is something that not even some computer spell check systems can get right. To be fair, this is pretty cool. You can make a computer learn to do plenty of things, but it will never score a 20/20 on its comprehension écrite. That being said, it goes to show just how many French writing rules are no longer supported by the modern day spoken language. The two verbs, ai acheté and ai achetees, are pronounced the exact same way.

But what’s this Académie’s whole deal anyway, and why does it seem to have a proverbial stick up its proverbial you-know-what?

How the Académie Française Came to Be

The year is 1635. The king is Louis XIII. Cardinal (de) Richelieu continues to exercise his control over the young king, and gets himself named “le chef et le protecteur,” or “Chief and Protector” of the newly created Acadmie Française. This novel language-governing body may be today’s most notorious, but it was not the first. Richelieu was inspired by Florence’s Accademia della Crusca, an Italian organization

The flowery language of the organization’s mission statement declares that the Academie’s function is to create certain rules for the French language that will render it “pure,” “eloquent,” and “capable of engaging with the arts and sciences.” The mission statement also likens a nation’s arts and sciences to its arms. This link between language and military prowess is a reminder that at the end of the day, l’Academie is still a government body looking to exercise power.

Given that the Académie Française was constructed during the monarchical phase of France’s history, you might be wondering about what happened to it during the Revolution. From 1795 to 1816, the Academie Française ceased to exist. Along with other royal academies, it was abolished by the National Convention before being reinstated by some guy named Napoleon Bonaparte. Since the dawn of the French Republic, the original role of “Le chef et le protecteur” is fulfilled by the sitting French President.

Who’s Who and What’s What

The Académie is made up of forty nerds members, know as Les Immortels. Some of these members have been literary powerhouses: Voltaire, Victor Hugo, Eugene Ionesco among them. To become a member, you have to apply to fill a vacant position, rather than applying to be a member in general. If someone is fit for the role, they are voted in by the current immortels. At meetings, members have to wear l’habit vert, a special green outfit. Funnily enough, the color green was chosen out of process of elimination, according to Henri Lavedan.

Over time, the organization has changed its mission to be a more holistic one, with the goal of creating a language and writing system that is to be used by everyone, not just arts and sciences hotshots. France’s national love for its languages means that L’Académie Française remains a culturally relevant part of the government. Whole swaths of people react viscerally whenever the Académie changes something, and it's not only French teachers who are startled.

Back in 2016, the Académie made it acceptable to leave the accent circonflexe (the carrot) off of certain words. They also recently changed the spelling of the word “onion” (from oignon to ognon) for some quirky reason. After some people expressed concerns about the changes, the academie has ensured that both old and new spellings will be considered “correct.”

More controversially, the Académie has also contested the feminization of French nouns. It insists that regardless of a person’s gender, they must always use the masculine form of a noun if there is no feminine form readily available. Le ministre will always be le ministre, never la ministre, regardless of the gender of the ministre.

Now, don’t get us wrong. Languages do need some sort of decided-upon rules for governing spelling and grammar (mostly spelling). But problems arise when these rules are decided by an elite group of educated people. It can create issues of class equality, with spelling rules easily becoming arcane because of natural changes in pronunciation. When spelling and grammar no longer reflect spoken language, and instead represent literary achievement, who do these rules really serve?

Thanks for Reading!

Thanks for reading this blog post. Next time you get upset about a mispelled word that still “looks right,” or are thrilled by a beautifully written French novel, you can thank the Académie Française. Be sure to give this post a “heart,” and to share it with a friend!

"C'est quoi, Dunkin'?" The French Language in New England

In New England, there’s more to French than just the fries.

by Brian Alcamo

When you think of New England, a few things may come to mind: fall foliage, seafood, and Dunkin’ Donuts. You might even think of (Old) England, with its linguistic, architectural, and cultural influences displayed all over the northern tips of the Eastern seaboard.

What you might not think of, though, is France. It turns out that the French language has a long-rooted history in the region (which, to be fair, also exists in England proper). French was originally part of New England way back in 1604, when the New France colony of Acadia (Acadie, en français) stretched into parts of present day Maine. It turns out that French culture in the United States isn’t limited to Louisiana.

The First Wave of Francophones

Almost a million French Canadians came to New England from the mid 19th to mid 20th century to work in the region’s many mills. The New England Historical society states that “Between 1840 and 1930, about 900,000 residents of Quebec moved to the United States. One-third of Quebec moved to New England to neighborhoods called Little Canadas.”

Historically speaking, French was discouraged by local English speakers, and tensions grew along both religious and linguistic lines. New England was historically home to a strong Puritan tradition, and the region’s staunchest Protestants were typically quick to defend the culture. Francophones often declared “Lose your language, lose your faith,” (“Qui perd sa langue, perd sa foi”) and French was upheld in many of the region’s Catholic churches. However, despite religious ties with the region’s Irish, the two groups did not get along.

Years after the industrial revolution’s end, a dip in Francophone activity occurred as many communities left New England and were conscripted to fight in World War II. WWII and its aftermath contributed to a new speed of assimilation of New England francophones. Many families left New England for both the war effort and for new career prospects as industry moved South and West (source). Despite these demographic changes, a francophone identity remained in Maine and other parts of New England. The culture stayed strong enough to even be part of the childhood of Maine’s previous governor, Paul LePage, who grew up speaking French.

A New Wave of Immigration

In recent years, cultural regeneration programs have begun to elevate French and Quebecois culture in New England, especially in Maine. Serendipitously, these programs have aided in the integration of new immigrants hailing from Africa.

These immigrants are typically asylum seekers from Angola and Congo. The state of Maine has been welcoming migrants with open arms, and is certain that the influx of new young adults and children will be a boon for the state’s economy in the long run. Though the rapid population increase has proved to be a challenge, many state officials are excited by the new diversity in the historically very-white state. Besides hundreds of new workers, the integration of these new francophones has led to a hopeful consequence: older Francophones now have a reason to use their language in a public setting.

These older white speakers who immigrated from Canada and younger black speakers who are now immigrating from Francophone African countries are using French to close generational and racial divides. Jessamine Irwin, a French teacher at JP Linguistics and Mainer says that she has “definitely found that French has been key in building bridges between the aging French speakers of Maine and the newly arrived French speaking African community.” While the intricacies of the dialect may change over time, the fact that French has remained and will remain in the region for a long time is a rarity, Jessamine says.

Planning a Trip

With New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine all being neighbors with Quebec, Canada’s semi-autonomous Francophone province, you can bet that frequent trade and travel occur between the two regions, whose histories have been and remain intertwined since European settlers arrived in North America. French can be heard all the time, especially during New England’s busy summer tourist season.

The tourist industry is even beginning to capitalize on the renewed interest in French-speaking culture, with a new initiative called the Franco Route starting up in 2019. The Lewiston Sun Journal reports that it is part of a new form of tourism called “heritage tourism.” The route runs south from the Twin Cities region of Lewiston-Auburn to Woonsocket, Rhode Island. Catherine Picard of Museum L-A has put together a two hour tour of the northernmost cities on the route, including sights of old mills and Franco-inspired architecture.

The official Franco Route website says that tourists will “discover the motivations, struggles, dreams and achievements of these newcomers” along with visiting “the museums, churches and genealogy centers that preserve this history, as well as the theaters, restaurants and microbreweries that creatively express that heritage today.” The route is a way to connect with the multicultural past and present of the United States, and is proof that people don’t need to leave the country to experience a certain je ne sais quoi.

Like This Post?

Make sure to share, and comment below what you think about practicing your French up North!

(Thumbnail photo by Mercedes Mehling)

French Tenses: The Recent Past and the Near Future

How to talk about what you just did, and what you’re about to do in French.

by Brian Alcamo

Here’s a situation:

You’ve just finished your first semester (or two) of French, and you’re looking to practice with a native speaker. Since no one can meet in person right now, you schedule a Zoom session. You’ve got your passe compose, imparfait, and futur simple memorized to a T, and things are going well (aka you said “bonjour” with a passable r). Suddenly, you hear a phrase je viens de sortir, which translates literally to “I come from to go out.”

“You viens de what?”

Or, in a different conversation, they say “je vais sortir,” which literally translates to the (more intuitive) “I am going to go out.” But maybe you’re still confused. Even though you’re not allowed to gather in public, you worry that sortir could be an amazing club that you’re missing out on.

“Where is sortir? Can I take the subway there?”

In the first conversation, it turns out that your friend is coming from nowhere, but they just went out. In the second, they are going out soon. Not only are you hurt because you weren’t invited, but you and your lost brain are now way behind in the conversation.

What tense did they just use?

Those two tenses are called the passé récent (recent past) and the futur proche (near future), and they’re both extremely useful in day to day conversation.

Luckily, even if you’re not physically coming from or going anywhere during times of corona, you can still practice conjugating the verbs venir and aller. That’s because French (and other languages, including English) uses the same verbs for movement through space as they do for movement through time.

A Refresher on Time

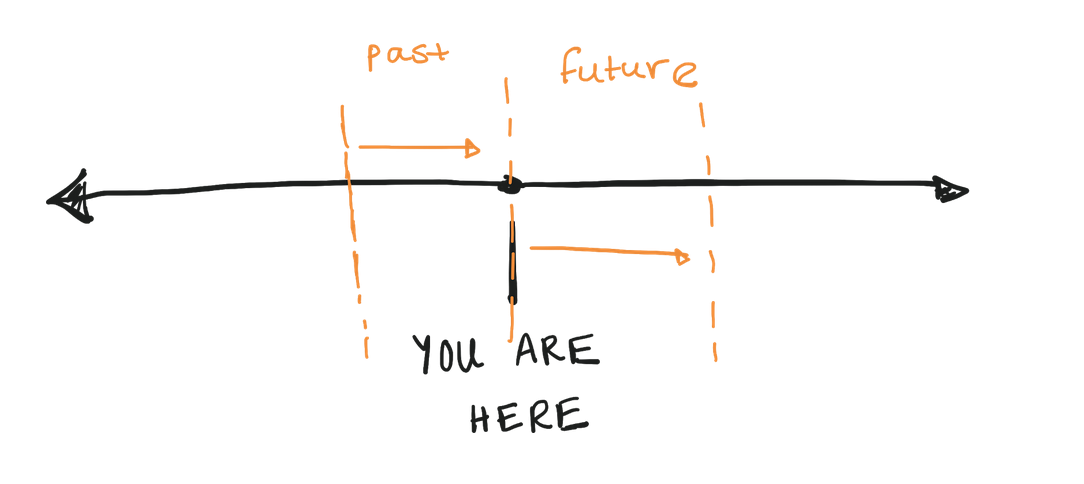

Before we talk about grammar, let’s try to get a grasp on time. No one can get a grasp on time, but let’s try. Pictured below is the present moment:

The recent past and near future (right before, and right after, you have a conversation) are pictured here.

The areas marked off in orange are where we’ll be spending most of our time for this discussion. The orange arrows are to show the forward motion that is inherent in the passé récent and the futur proche. Don’t fret that there are no easy to use verbal constructions for talking about movement back in time. We doubt you’ll need to talk about the process of unbrushing your teeth or ungoing to a party (unless you’re writing a scifi/fantasy movie, in which case, our headshots are ready).

Now that we’ve got time as figured out as possible, let’s talk about tense #1, le passé récent.

Le Passé Récent

The passé récent is formed with venir + the preposition de + a verb in its infinitive form. It’s used to mean that you’ve just done something. Here’s an example:

Je viens de quitter le bureau. “I just left the office”

The French textbook Contraste: Grammaire du Français Courant calls venir a “semi auxiliary,” which is a verb that sometimes behaves like an auxiliary verb. Être and avoir are examples of true auxiliary verbs.

Here’s a refresher on how to conjugate venir in the present tense.

Je viens “I come”

Tu viens “You come”

Il/elle/on vient “He, she, we come”

Nous venons “We come”

Vous venez “You (pl) come”

Ils, elles viennent “They come”

If you’re telling a story and using the past tense, you would simply conjugate venir in the imperfect, saying something like:

Il venait de quitter le bureau or “He had just left the office.”

If you’re having trouble wrapping your head around it, think about it as if you’re walking on a timeline. You’re “coming from” the activity that you just did right before the present moment.

Now that we’ve come into the present from the past, let’s continue into the future with the futur proche.

Futur Proche

In the futur proche, you use the verb aller which means "to go.” You conjugate aller and tack on an infinitive. In this construction, aller functions as a semi-auxiliary verb, just like venir in the passé récent.

So "Je vais danser ce soir," means "l'm going to dance tonight." (Sounds fun!)

In case you need it, here’s a quick repeat of how to conjugate aller in the present tense:

Je vais “I go”

Tu vas “You go”

Il, elle, on va “He, she, we go”

Nous allons “We go”

Vous allez “You (pl) go”

Ils, elles vont “They go”

The future proche is a bit more flexible than the passé récent, because you can say that you're going to do something pretty far into the future. "Je vais aller à Lyon dans six mois" ("l'm going to go to Lyon in 6 months") is a perfectly acceptable sentence. This is because the futur proche can also convey a meaning of intention. With regards to its cousin the futur simple, things stated in the futur proche are usually thought of as more certain to happen.

There are a few other phrases that can be used to convey a similar meaning to aller + infinitive:

être près de + infinitive - “to be close to”

être sur le point de + infinitive - “to be on the verge of”

s’apprêter à + infinitive - “to be about to”

avoir l’intention de + infinitive - “to mean to”

If you're telling a story and using the past tense, you can conjugate alter in the imperfect and add an infinitive, saying something like:

“Nous allions sortir en boite, mais il a commencé à pleuvoir”

“We were going to go out to the club, but it started raining.”

In the past tense, this structure conveys a sense of planning that gets interrupted. Notice that even though you’re using aller to talk about this plan, you’re conjugating it using the imperfect tense, and throwing that futur straight into the past.

Devoir + infinitive when used in the past tense has a similar meaning to the futur proche in the past tense. The meaning here is “was supposed to” or “must have.”

Getting a grasp on time is tough, and the current environment of social distancing has left many people struggling with how to keep track of it. The passé récent and futur proche are wonderful examples of how our brains use the same structure for movement through time as they do for movement through space. And as with a lot of movements, the only way “out” is “through.”

Merci !

We hoped you enjoyed this blog post. Be sure to “heart” it, and to share with your friends. Keep the conversation going in the comments.

Want to review what you learned? Take our quiz down below!

(Thumbnail Photo by Djim Loic )

Making French Mandatory

A fight for linguistic dominance is emerging in Ghana, and French’s future in the country is at stake.

Since achieving it’s independence from the British in 1957, Ghana has had strong ties to the English language, and most of it’s citizens who’ve been through some level of formal education speak English alongside their regional language. However, Ghana’s president Nana Akufo-Addo is now actively campaigning for Ghanaians to also learn French and one day make it the country’s official second language.

Akufo-Addo descends from a Ghanaian political aristocracy with long ties to Britain and was partly educated in England from a young age, but he also speaks French fluently which has lead him to push for French to become a requirement for high school students and in a 2018 speech which was given entirely in French.

Akufo-Addo’s support for French comes as France’s president Emmanuel Macron is also making a soft power push to raise the status of French across Africa, starting with former French colonies. In March, he stated, “As France represents only a fraction of the active French speakers, the country knows the fate of French language is not its burden alone to carry.”

While it may be obvious that the push for French in Ghana has a lot to do with the president’s personal affinity for the language, there is good reason for increasing the number of Ghanaians who can speak French. All of Ghana’s immediate neighbors use French as their official language and in the wider Ecowas regional block, eight out of 15 member countries are Francophone. A “bilingual Ghana”, strategically positioned, could stand to benefit economically from ever closer ties with her neighbors.

In recent time, teen students in Ghana have had to take a French language exam as part of a national exam that allows students to progress to high school but has failed to translate into a considerable number of citizens being able to communicate in French fluently. There is also the social aspect that is tied in with the history of colonialism in Africa., However recently, the reservations have not been about French, but instead about Mandarin and China’s increasing economic and political influence as countries including Kenya, Uganda and South Africa are all introducing Mandarin into their schools’ curriculum.

Last, there is the issue of local languages being lost forever. It is estimated that at least a dozen Ghanaian languages have been lost over the past century and about a dozen more have less than 1,000 speakers. While almost a third of Ghana’s indigenous languages have less than 20,000 speakers and rapid urbanization and global influence may mean the languages risk extinction, it will be up to the keepers of these languages to document them to allow them to continue to flourish alongside whichever foreign language may be introduced to the formal schooling system.

The Newest Language Learning App

Connect and learn 8 Romance languages at once, all from your phone!

The French Ministry of Culture has just launched its a brand new application called ‘‘Romanica’‘ that features 8 Romance languages on all mobile devices. The theme of the app includes greetings, time, travel and arts, and the central aspect of the game teaches that learning doesn’t have to be a daunting task as the languages are not very different.

The French minister of culture, Franck Riester stated that “This game is a way of bringing together languages and cultures…(&) shows everything that unites us.” Currently, the app is available for free on download platforms and partnership is expected to be formed between the game producers and the French Ministry of National Education. This would allow Romanica to be used in schools for learning languages thus making the languages more accessible to students earlier in life.

The initiative was praised by the Romanian Ambassador to France who welcomed this interest in languages via by mobile technology.

We hope you’ve enjoyed learning about The Newest Language Learning App! Looking to hone your linguistic skills? Our culturally immersive group classes and private lessons will put you on the path to fluency faster than you may think! Click below to learn more.

New French Feminine Lingo To Learn

New French words to finally reflect the number of women in the workplace.

The French language is set to undergo quite the transformation after the council charged with safeguarding the French language abandoned it’s opposition to the feminization of job titles.

The Academie Francaise, or “French Academy,” has declared in a new report that the 36-member body saw “no obstacle in principle” to feminine versions of French words for professional titles and that they were open to “all developments in the language aimed at recognizing the place women have in society today.”

The French Academy was established in 1635 under Louis XIII and hasn’t made any decisions regarding the matter since 2014, when it ruled that the mayor of Paris was guilty of crimes against grammar by championing a gender-neutral version of her job title. While feminine versions of job titles, although technically unofficial, are already used widely in France, and several French-speaking countries such as Canada have already embraced feminizing nouns when appropriate.

Unfortunately the proposal was not welcome news for many French language purists. MP Julien Aubert recently tweeted that "For the first time in its history, language was reshaped under the pressure of politicians and lobbies, and the Academie Francaise eventually surrendered.” While the ultimate fate of these linguistic changes are still to be determined, the cultural impact will be certain.

Looking to avoid as much confusion as possible in your French linguistics journey? Our native instructors and immersive group classes can help you make sure you are up to to date on all of the new lingo! Click below to learn more.

Au Revoir Smartphones!

Say hello to “multi-function mobiles!”

The French people as a whole are very proud and protective of their culture and customs (as referenced in our previous article, Battle of the Baguette), and there is no exception when it comes to the language itself. In an effort to avoid the “Englishification” of their language, officials in France have been coming up with alternatives to many of the most popular phrases of our current digital age.

In the past, the official journal of the French Republic, the Journal Officiel, has suggested “internet clandestin” instead of the term dark web. The very popular word, hashtag is called “mot-dièse” or “hash-word.” The latest word to get the official "Au revoir" in France is the term, smartphone thus giving way to “le mobile multifonction.”

This proposal is headed by the Commission d’enrichissement de la langue française & Academie Française to preserve the French language, and it isn’t the first time that they’ve encouraged French citizens to switch over to Franco-friendly words for tech products. Instead of smart TV, for instance, the commission suggested that French speakers say “Televiseur connecté.” A relatively straightforward translation was offered for net neutrality: “neutralité de l’internet.” Previous suggestions for smartphone have included “ordiphone” from “ordinateur,” the French word for "computer" and “terminal de poche” or "pocket terminal".

Today’s protectors of the language may be mostly concerned with emerging tech terms, but the battle against English influence has been waged for decades as France’s first committee to protect the country’s vocabulary was established in 1966: The General Delegation for the French language and the languages of France ("Délégation générale à la langue française et aux langues de France.”

What do you think about the Commission d’enrichissement de la langue française & Academie Française's attempt to say "Au Revoir Smartphones?" Leave a comment below!