The University of Bologna: A Brief History

In case you weren’t already overthinking going back for Grad School.

La Piazza Maggiore in Bologna

by Brian Alcamo

Students are heading back to classrooms after a summer of fun. For some, the break from the classroom has been even longer, with in-person learning being replaced by remote alternatives to circumvent pandemic lockdowns. While universities have been around for a long time, one has stood the test of time longer than all the others. Italy’s University of Bologna, l’Universitá di Bologna, is both the oldest and longest-functioning university in the western world, and its storied history is fascinating. Find out more below!

The Beginning

The University of Bologna is considered by most to be the first Western university, with scholarly activity dating all the way back to 1088 C.E. First founded as the (private) School of Bologna, the historic place of learning coincided with the establishment of the Studium of Bologna. Because of a collective of a few dedicated students, the School of Bologna’s ascent as a leading site of learning began to coincide with the city’s growth as an economic powerhouse. By the 12th Century, the city had transformed from being known as La Dotta (The Learned) to La Grassa (The Fat), due to its rapid rise in wealth. Once il Comune (the municipality) realized that the school was attracting young wealth, it began to enact policy aiming to protect and favor the school. Private homes, monasteries, and public areas were rented out to provide adequate space for the droves of new learners. This created a robust, geographically decentralized network of educational nodes, differing from the typical “campus” model that many Americans are familiar with today.

Bologna’s Archiginnasio, which was not yet built at the university’s start

The 13th century saw the University's graduates’ reputations on the rise, especially its Law School and Art School students, who were seen as providing foundational legal and cultural foundations for an emerging European society. Law School students formed organizations meant to establish a system of mutual support. These were originally based on students’ place of origins (known as Nationes) which slowly turned into guilds known as Universitates.

A Change in Power Dynamics

The fourteenth century saw a tightening of student and teacher autonomy as the Comune placed more controlling decrees on the school. Teachers became public employees and their performance declined with their academic fate coinciding with the shifting economic winds of the city. During the fifteenth century, the school’s fame helped maintain its student body while its arts program was reinvigorated with Renaissance ideas. This century was also the height of Bologna’s Bentivoglio family, and teachers began to be effectively “bought out” by the wealth of the city’s de facto lords. This newfound corruption led to the erosion of both the university and the commune’s freedom.

Vocabulary for Your Next Semester in Italia

Semestre - Semester

Il programma di studio - Syllabus

Il compagno di classe - Classmate

Studiare - To study

Consulente academico - Academic advisor

Esame - test

Tema, saggio - essay

In the sixteenth century, The Council of Trent and the construction of the Archiginnasio Palace both ended up driving out students, with the Palace replacing the school’s geographically decentralized nature as a one-stop-shop location for University activity, becoming an easily governed location where Papal Rome could impose Catholicism on the student body. After these reforms, the school’s performance saw a two-century lull, with the seventeenth and most of the eighteenth century seeing little innovation and being left out of the rest of Europe’s Renaissance fun. The sad ship began to slowly (and we mean slowly) turn around with the new Academy of Sciences of the Institute of Bologna, which provided a space for critiquing the Church and aristocracy.

The Library at the Institute of Sciences

Back in the Saddle

Interestingly enough, the University saw a Renaissance of its own when the Italian peninsula came under control of Napoleon Bonaparte’s French Empire. The Studium became a public university and moved its center of operations to the Palazzo Poggi, which brought a new artistic and cultural center to Bologna. Unfortunately, when the French Empire receded and the papacy was restored, many changes were repealed.

Il Risorgimento, or the Italian Unification, finally brought respect and prestige back to the Studium, when forces at the helm of the unification sought to construct the narrative of a common Italian history. Bologna had once again become one of the most important cities in the new country.

In the twentieth century, the university began to occupy historic buildings around the city, positioning itself as a fulcrum of urban life. In 1988, a celebration of the university's ninth century reinforced the school’s reputation as a location that honors the independence and freedom of teaching and its history as the Alma Mater Studiorum.

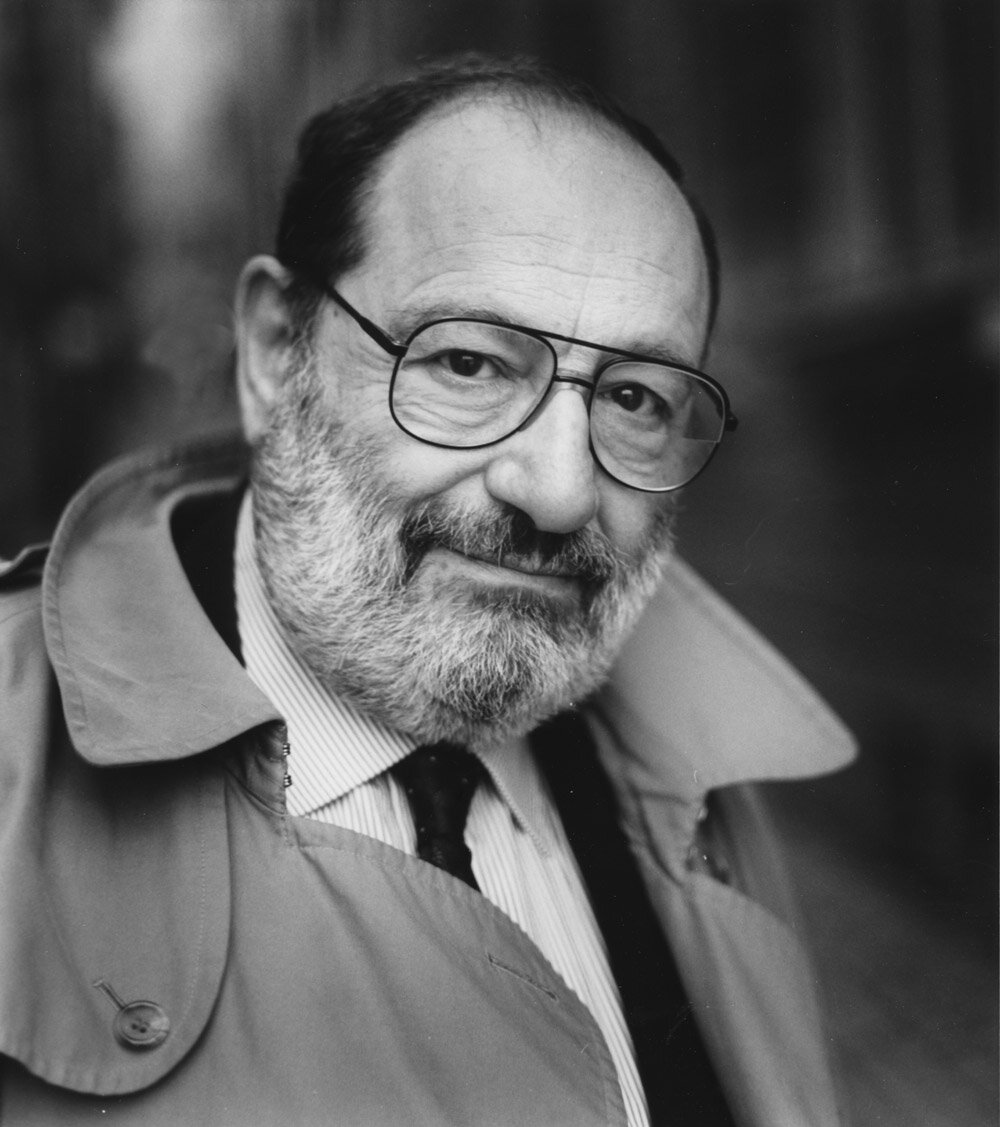

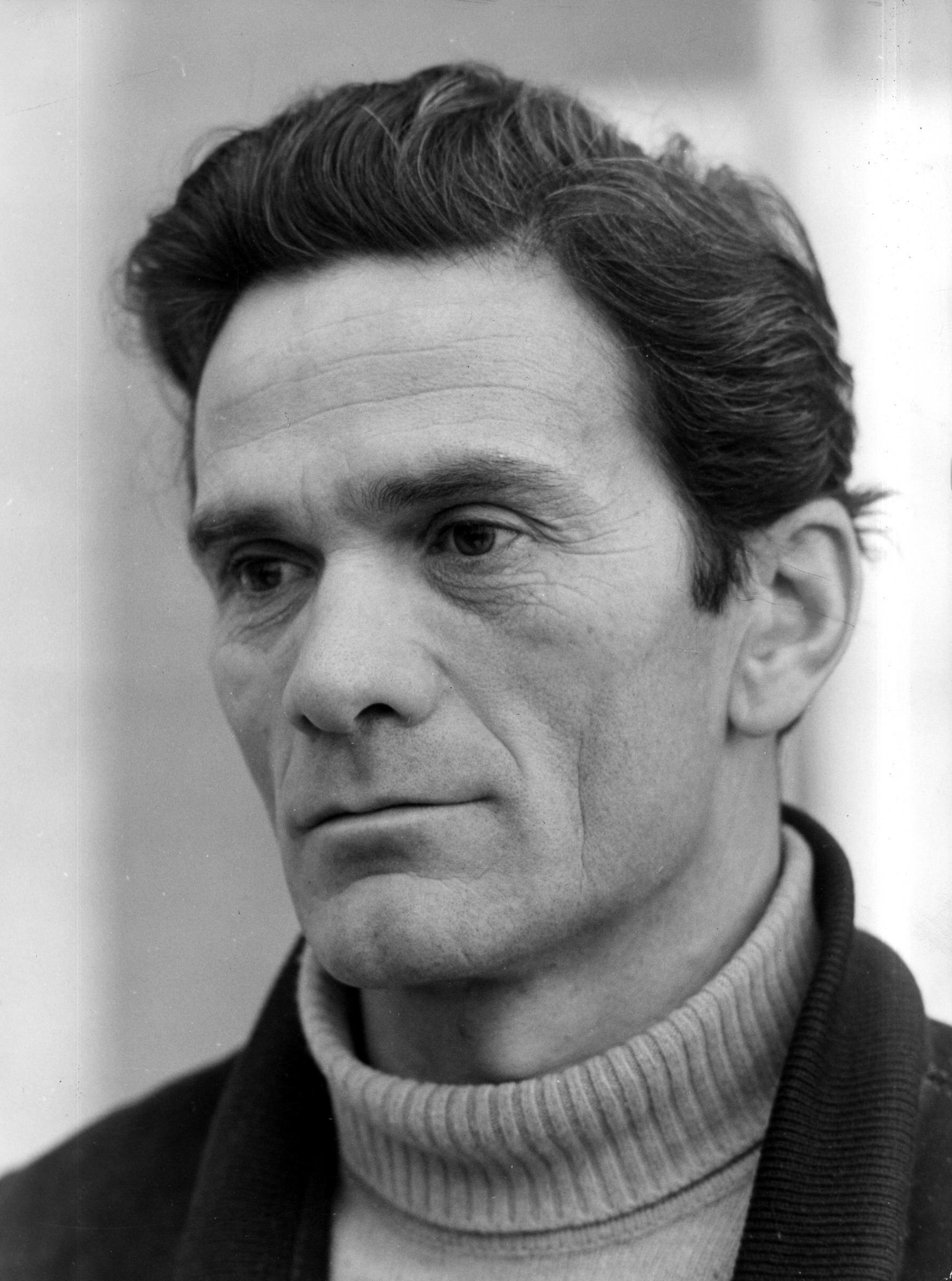

Some Famous Alumni

The University’s status as an important site of educational patrimony was further cemented in 1999 when European diplomats came to the University to sign the Bologna Declaration. This signing established the Bologna Process, a series of meetings with the purpose of establishing and maintaining higher-educational compatibility between European countries. The Process follows a qualifications framework that uses the university levels of Bachelors, Masters, and Doctoral degrees as guidelines for determining educational achievement (according to the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System, or ECTS).

Nowadays in the twenty-first century, the university has expanded outwards into Bologna’s suburbs, moving the locations of its course offerings. It also has created the first multicampus in italy, with satellite campuses throughout Emilia-Romagna.

Thanks for Reading!

Want to go back to school? Learning Italian provides you with the skills you need to make education in Italy a real possibility. Comment your study plans below, and be sure to share this post with a friend!

Avocados: A New Staple of Sicilian Cuisine?

by Brian Alcamo

When you hear the words “mangoes,” “avocados,” and “bananas,” what places come to mind? Costa Rica, with its lush rainforests capable of watering these thirsty fruits? Mexico, where avocados originate? Or even Florida, where plentiful year-round rainfall and high temperatures keep vegetation quenched and satisfied? All of these places are good first thoughts, but there’s another place that climate change has transformed into a new growing zone for these tropical treats: Sicily.

In recent years, Sicily and the rest of Southern Europe have been forced to acclimate to increasingly hot summers. While Sicily has always been prone to high temperatures and scorching hot summers, the thermometer has recently been reading higher than most people can bear. In fact, the island may have just recorded the hottest temperature in Europe ever.

In Floridia, a town near the ancient Sicilian city of Siracusa, a weather monitoring station registered a temperature of 119.84 degrees Fahrenheit (nearly 49 degrees Celsius) on Thursday, August 12th. Not only was the day a sure-fire sweat fest, people in the town reportedly felt sick from the heat.

Floridia isn’t the only city in Italy to experience these blisteringly high temperatures. All of Italy has been engulfed in a scorching summer swelter for the past few weeks, with places further south suffering the worst effects. Not only are they uncomfortable, but these increasingly common heat waves are also not-so-slowly reshaping the Italian agricultural ecosystem.

Workers in the agricultural sector have a particularly up-close vantage point for observing how climate change will impact our diets. Floridia’s iconic snail farms have been ruined by the heat, with their livestock being practically cooked before shipping. Citrus groves aren’t faring too well, either. In response to the recent destruction, some farmers have begun planting tropical fruits that are more adept at surviving through high temperatures.

One farmer, Andrea Passasini, replaced his grandfather’s vineyard, which overlooks Sicily’s Mount Etna, with an avocado grove. “Avocados?” you may ask. Yes, the fruit indigenous to Mesoamerica has finally made its way to Europe. While various crops from the Americas moved over to Europe during the centuries-long event known as the Columbian Exchange, the avocado is a newcomer in the game.

Passasini’s farm is located in Giarre, where he has identified a microclimate perfectly suited for tropical fruits. This new climate zone makes growing tropical fruit all the easier, with new growing locations for avocados and mangoes springing up all the time. He produces roughly 1.4 tons of avocados per year, and his success has encouraged other Sicilian farmers to do the same. In addition to growing avocados, Passasini also grows passion fruit, and he thankfully continues to care for decades-old lemon trees.

Vocabulary to Follow Along With Italian Agricultural Happenings

L’agricoltura - Agriculture

Tropicale - Tropical

Prodotti agricoli - Produce

Contadino, agricoltore - Farmer

Cambiamento climatico - Climate change

While a few farmers such as Passasini have benefited from the change in growing zones, the shift has spelled economic disaster for others. Some farmers see this shift as an opportunity, taking advantage of new growth patterns, while those who haven’t changed their tune have unfortunately gone out of business in recent years. Even farmers trying to adapt to new climates have struggled to keep up with increasingly erratic weather patterns. Extreme weather events including hail, heatwaves, and tornadoes have made any kind of agriculture less predictable, regardless of whether the crops in question can withstand the new temperatures. Sicily’s already short winter which used to arrive in late December is now more of a February event. Ettore Prandini, the president of Coldiretti, the Italian farmers’ union, notes that every year brings longer-lasting episodes of sky-high temperatures and tropical weather patterns.

In general, the Mediterranean basin is poised to suffer dramatically from climate change, with countries in both Southern Europe and Northern Africa gearing up for a drastic decline in rainfall. This creates an agricultural conundrum, whereby high temperatures encourage the growth of tropical fruits and vegetables but falling rain estimates prevent their need for lots of water. If Sicilian farmers want to succeed in the future, they’ll have to invest in large irrigation efforts.

Forget the future. Italy’s agricultural regions have already undergone major shifts. Mangoes, avocados, and bananas coexist amongst oranges and lemons in Sicily, and olive trees now thrive in the once-frigid Alpine valleys up North in Lombardy. Particularly sensitive to temperature changes are wine grapes, with the crops being seen as a sort of whistleblower to changes on the whole. Research has shown that a 2 degree C rise in temperature would cause 56 percent of the world’s wine regions to become unusable. This also means that some regions, like Canada’s Niagara Peninsula, have recently been able to step up their viticulture game. Grapes can no longer thrive in the way they need to for sustaining a business. Further up Mount Etna, temperatures drop low enough to continue growing them… for now.

While it may seem strange to some to bring a crop across hemispheres, blockbuster knockouts such as “Tomato” and “Potato” have their original roots in the Americas as well. Imagine Italian food without pomodori or patate, it’d be stange, wouldn’t it? Imagine a future where avocados and mangoes are staples of Italian cuisine, it sounds improbable, but could very well be the case. Sure enough, we bet someday soon restaurants will be serving delicious avocado pestos that they’ll claim to have invented. Imagine what avocado could bring to Italian cuisine. Soon, you’ll be able to say “wow, this Italian mango is delicious!”

Learning Italian will help you navigate these changes with ease so you can stay on top of all the newest and best Italian food products. While climate change is nothing to smile about, at least a few Italian farmers are trying to innovate and thrive with the conditions that they’re facing. Out with the old, in with the new. When life gives you avocados, make toast!

Thanks for Reading!

Excited about the idea of mango-infused Italian dishes? Scared about the perils of climate change? A little bit of both? Comment your thoughts below, and be sure to share this post with a friend!

Pesto: An Ode to Ligurian Basil

What’s lean, green, and filled with garlic?

Photo by Nathalie Jolie

by Brian Alcamo

Pesto! It’s green, it’s garlicky, and it’s delicious to anyone who isn’t allergic to pine nuts. You can put it on pasta, sandwiches, and anything else you deem “pesto-able” (though some hard-core Italians would beg to differ). For anyone interested in learning Italian, an investigation of this sauce is in order.

Where is Pesto From?

Unlike many recipes, the region of origin of pesto is usually agreed upon to be Liguria, specifically the city of Genova. Liguria is a region in northern Italy, sharing a border with the French region Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (which includes Nice and other cities that make up the French Riviera) to the West, Piedmont (Turin’s region) to the North, and Emilia-Romagna (the region of Bologna) and Tuscany (the home of Florence) to the East. Liguria is the home of the Italian Riviera, where its capital city Genova and others including Savona, Imperia, and La Spezia form a continuum with its French counterpart.

Liguria is not only gorgeous, it also features a climate and seaside soil rich in minerals that make it the perfect location for cultivating basil, a key ingredient in pesto. The city where a lot of this basil cultivation takes place is Pra’. Ligurian basil is known for its mild, aromatic flavors imbued with sea-like qualities. It’s said that basilico genovese needs to “see the sea” in order to grow. The leaves are plucked when they’re young, and are thus smaller and more delicate than most basil varieties seen in the US. This gives the basil more delicate qualities. If you’re having trouble imagining what these leaves might taste like compared to a larger ‘Merican cousin, think of “baby” varieties of your favorite lettuces: “baby” kale versus mature kale, “baby” arugula versus mature arugula, etc.

The word pesto comes from the Italian verb pestare, which means “to pound” or “to crush.” This etymology most likely stems from the fact that pesto was traditionally with a wooden pestle and marble mortar. Pesto’s history goes way back in time, all the way back to the ancient Romans, who ate something called moretum, which was a green paste made from cheese, garlic, and herbs. By the Middle Ages, moretum had evolved into a new sauce called agliata, which was a sauce made of walnuts and garlic. Garlic has a special place in the hearts of the Genovese, especially as a medicinal agent adored by the city’s seafarers. It was in the 19th century that the recipe for what we now know to be pesto began to appear in Genovese documentation. The 1863 cookbook La Cuciniera Genovese published by Giovanni Battista Ratto features a recipe calling for the following ingredients:

A clove of garlic

Basil (or marjoram or parsley as a substitute)

Grated dutch and parmesan cheese

Pine nuts

A little butter

The ingredients were to be mashed with a pestle and mortar until smooth, then diluted with olive oil. Lasagna and gnocchi were to be dressed with the sauce which could be thinned out to-taste with hot water. Dutch cheese was used instead of pecorino because it was more available due to the Genoveses’ trade relations with the residents of the Netherlands.

In the 1800s, pasta al pesto was considered a dish of the working class. Ligurians still add potatoes, broad beans or French beans, and small pieces of zucchini boiled together with the pasta in this dish. These ingredients are often added to trenette, a type of dried genovese pasta. Some pesto makers add walnuts and even ricotta. These pesto variations prove that no Italian recipe is set in stone, and that culinary innovation is happening all the time.

Vocabulary for your venture into pesto-land

Garlic - aglio

Pine nuts - pinoli

Basil - basilico

To grind - macinare

Sea salt - sale marino

Pesto Today

Pesto began to become a global phenomenon after the Second World War. Over time the ratio of basil to garlic has changed, with older versions of recipes using way more garlic than basil, sometimes even only three or four leaves of basil compared to three or four cloves of garlic. This kind of pesto fit the tastes and culinary fashions of the Genoese, highly influenced by Arab and Persian costumes starting in the Middle Ages and continuing until the 1800s. It also helped to continue the Ligurian tradition of making sure the region’s sailors were well-stocked with garlic. Nowadays, pesto contains much more basil, and has a more balanced flavor.

When preparing a pesto, it would be both elegant and wonderful if you could use the highest quality ingredients as if you were a true Ligurian: Regional extra-virgin olive oil, Vessalico garlic, Italian pine nuts, and salt from the Cervia salt flats. Barring access to all of these authentic ingredients that are hard to find outside of Italy, the best you can do it find your own quality ingredients and follow an original recipe. If you’re looking to grow your own basil for pesto, try ordering from Seeds From Italy to get as authentic a source as possible. If you want your pesto to be as authentic and hand-crafted as possible, opt for a mortar and pestle as opposed to using a food processor. Pestle and pesto go hand in hand!

Not looking to make your own pesto? That’s okay too! Just remember that every bite of your favorite pesto-infused dish carries with it the traditions of a region of proud seafaring Italians.

Thanks for Reading!

Be sure to share this article with a friend, and comment below your favorite things to dress in pesto!

Here's The Skinny on LGBTQIA+ Rights in Italy

Ever wondered what Italian law has to say about LGBTQIA+ individuals? Get the facts here!

by Brian Alcamo

Italy is known for so many fabulous things: historic artwork, breathtaking landscapes, and mouth-watering food being a few. What you may not think of when you hear the word “Italy,” though, is Queer rights. While Italy only legalized same-sex civil unions (not marriage) back in 2016, its history of queer rights and discrimination is rich and complex.

Back in 1805, the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy, the Kingdom of Naples, and other French client states in Europe adopted the Napoleonic Code which effectively legalized homosexuality. However, in 1815, Napoleon lost his grip on Italy and the previous monarchies were gradually restored along with their previous codes of law that banned homosexual activity.

In 1859, the Kingdom of Sardinia changed its laws to criminalize homosexual acts between men. As it so happens, the Kingdom of Sardinia is the Kingdom that spearheaded Italian unification (il Risorgimento). As it was unifying Italy, the Kingdom was also unifying Italy’s laws. When the system of law changed, homosexual acts between men became illegal throughout Italy. The only region where this law was not put into effect was in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, which avoided the law because the new government was taking into account “the particular characteristics of those that lived in the South.”

In 1889, homosexuality was decriminalized with the arrival of the Zanardelli Code, started by Justice Minister Giuseppe Zanardelli. As long as it did not involve violence or “public scandals,” homosexuality was not punishable by law. That being said, homosexuality was considered a “sin against religion or privacy.” The new code, while it did keep homosexuality out of the eyes of the law, also worked to create a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy when it came to being gay. Unwittingly, some cities still took advantage of the new legal gray area, with Venice turning into— dare we say it was “popping off” as— the European gay destination of choice.

This policy continued on in the 1930s when a new code was introduced alongside Italy’s new fascist regime. The new Rocco Code reinforced a “don’t ask, don’t tell” spirit surrounding homosexuality in Italy not out of a nascently inclusive agenda, but because Italian fascists wanted to deny the existence of gay people in the country. The code read that “It will not be punished because the vicious vice of homosexuality in Italy is not so widespread that it requires legal intervention.” This left persecution of homosexuality up to the Catholic Church.

“Where are they now?”

Despite this “out of sight, out of mind,” relationship that exists between queer people and the Italian government, some progress has been made since the turn of the millennium. In 2003, the entire country of Italy made discrimination based on sexual orientation illegal in compliance with EU guidelines. Tuscany became the first Italian region to successfully implement legislation that prohibits discrimination against homosexuals (in the domains of education, employment, public services, and accommodations). This legislation was challenged at the national level, and eventually the section of the law mentioning accommodations was removed while the rest of the legislation remained intact. Piedmont enacted a similar law in 2006. Same-sex civil unions were made legal in 2016.

The Catholic Church is still making life difficult for queer Italians. While protections against racial and religious discrimination have been codified, protections on the grounds of gender and sexual orientation have yet to be put into effect. A large force in this delay is the conservative political party Brothers of Italy which represents the country’s Catholic bishops.

Italian Vocabulary For Talking About Queer Rights

I diritti - Rights

Omosessuale - Homosexual

Arcigay - Italy’s biggest LGBTQIA+ activist group

Identità di genere - Gender identity

Orientamento sessuale - Sexual orientation

Back in 2020, a new law, known as the Zan Bill, was being cooked up by the Italian government to begin protecting people based on their gender and sexual orientation. A priest in Puglia, a region in Italy’s Mezzogiorno (the South) even held a vigil to pray that the law would fail. The law, was approved by Italy’s lower house of parliament back in early November of 2020. It saught to “integrate an existing law and extend protection to women, LBGTQ+ and people with disabilities from discrimination based on gender identity and expression, sexual orientation, ableism.” Many people were not pleased.

While the Italian Senate continues to examine the Zan Bill, the Vatican has decided to voice some concerns, saying the bill attacks the Italian Catholic community’s freedom of beliefs. Whether the Zan Bill will pass in the Senate is still unknown, but make sure to check out some Italian news sites to brush up on your Italian and keep up with the latest happenings.

Thanks for Reading!

Were you surprised to learn about Italy’s Queer rights history? Comment below, and share this article with your Italy-loving friends.

Thumbnail photo by Luis Cortés.

Scopa: A Simple and Fun Italian Card Game

Discover a game that’s both easy to learn and easy to argue about.

by Brian Alcamo

Italy is a land of many national pleasures. Limoncello, opera, and tiramisu are just three examples of the myriad Italian treasures. But the country has cultural mainstays that go beyond globally recognizable exports. Italy is home to more than just highly refined handicrafts. In fact, this bel paese is home to not just one, but three, national card games. While they might not evoke the same cultural reverie as Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, giochi di carte (card games) have sustained their presence in Italy through the centuries.

Card games are a big part of Italian culture, and they’re a great way to spend more time around the dinner table after the eating is over. A few years ago, I was lucky enough to spend an evening with a friend’s host family in Florence. We played Scopa, an Italian card game, after dinner and before dessert. By the end of playing, my Italian was way better than it was during the meal. Without food in our mouths, we were able to have a more fulfilling conversation that wasn’t happening in between bouts of chewing.

Scopa, Italian for “broom,” is a fishing-style card game that involves “capturing” cards from the table by matching table cards with the cards in your hand. Along with Briscola and Tressette, Scopa is an Italian card classic. The game is fast-paced, easy to learn, and hard to master. It makes for a perfect night of relaxing with friends and family around a table. Read on to learn more!

Italian Decks of Cards

Before you play Scopa, you have to make sure you have the right deck of cards. Decks of cards, or mazzi di carte, are a little bit different in Italy. For starters, these decks typically only have 40 cards. They eschew the 11, 12, and 13 values of Jack, Queen, and King for suits that end at 10.

Speaking of suits, very few Italian decks of cards use suits that are “Italian” in origin. Most in the North use French suits, and most in the South use Spanish suits. Italian suits are only prominent in the Northeast of the country around Veneto. In a typical 40-card Southern Italian deck: 4 suits: spade (swords), coppe (cups), ori/denari (coins), and bastoni (batons). Italian and Spanish suited share the same names, but use different pictures. Each region uses its own special set of cards.

Your cards probably won’t be this antique, but it’s worth aspiring to this level of authenticity anyway.

In cities north of and including Florence, most players use French cards. French cards are the 52-deck playing cards that most Americans and Brits are used to using. To adhere to the game play of Italian card games, players remove 3 cards from each suit, paring the 52-card deck down to a 40-card one. The Italian names of French suits are: Cuori (Hearts), Quadri (Diamonds, directly translated as “squares”), Fiori (Clubs directly translated as “flowers”), and Picche (Spades, literally "Pikes").

Unless you own an Italian deck of cards already, you’ll probably have to take out cards from a pack you already own. Once you’ve gotten yourself a Scopa-appropriate deck, it’s time to play!

Playing

Scopa is played for points. At the beginning of each game, players must agree on the winning number of points. A common goal score is 21.

To start, the dealer gives each player 3 cards (face-down) and places 4 cards (face-up) in the middle. Players try to capture cards from the face-up cards in the middle. They can either make a direct match, or (even better) match the value of one of their cards with the sum of multiple cards on the table. For example, if there are two cards on the table that add up to 8, and a player has an 8, that player can take both cards to create a match.

If you take all 4 cards on your turn, congratulations! You get 1 point for a successful scopa. Once everyone runs out of cards, the dealer deals players three new ones. A hand ends when the deck of cards runs out. This is when you score points.

Don’t be fooled by the game’s simple rules! Things can get competitive.

Scoring

1 point for each scopa

The player with the most cards gets 1 point. In the case of a tie, no one gets points.

The player with the most diamond (or coin) cards gets 1 point. In the case of a tie, no one gets points.

The player with the 7 of diamonds (Il Settebello) gets 1 point. In the case of a tie, no one gets points.

The player with the best primiera (prime) scores 1 point. A primiera is a set of 4 cards, one from each suit. If you don’t have one card from each suit, you’re not eligible to score a primiera. A primiera can be scored in multiple ways. Two common ways are whoever has the most 7s and who has the highest score based on a hard-to-remember chart that you can find here.

If no one has enough points to win, gameplay continues, and the deck is shuffled and dealt again. Play until one player has enough points to score.

Play With Friends!

Scopa is a fun and easy-to-learn card game that will keep you and your friends up into the wee hours of the night. Modify the rules as you see fit, and maybe even buy one of those beautiful Italian decks of cards to upgrade your game. Don’t forget to practice your Italian around the table as you play!

What’s your favorite card game? Comment below, and share this post with a friend.

(Thumbnail photo by Inês Ferreira)

Perfetti Sconosciuti and Technology’s Disruptive Role in Friendships

Scandals and secrets abound in this Italian comedy-drama.

by Brian Alcamo

Do you ever think about how technology is disrupting your most intimate relationships? Maybe not recently, since online communication has been one of the key parts of staying sane during the pandemic. Even still, phone dings and Instagram pings can interrupt more than our workflow, they weasel their way into every conversation we have. Some of us still struggle to not check social media even when on a Zoom call. Notifications and the impulse to refresh our feeds normally simply erode our attention to the present moment, but in the movie Perfetti Sconosciuti, they end up bringing people together, if only to quickly push them apart.

Perfetti Sconosciuti (Perfect Strangers) is a 2016 Italian film directed by Paolo Genovese that follows seven close friends as they share a meal and learn more about each other than they have in years. You might think that a movie set entirely at dinner sounds boring, but dinner isn’t the star of the show here, it’s technology. What starts as a friendly meal turns into a social experiment when Eva, played by Kasia Smutniak, decides to play a game with her and her husband Rocco’s (Marco Giallini) friends.

The rules of the game in Perfetti Sconosciuti are simple. If someone’s phone buzzes, everyone else at the table gets to know every detail of the notification. Things start out simple enough, with little text messages sparking tiny rifts in friendships. It doesn’t take much time, though, for the real secrets to start spilling out. Lies, deceit, and evidence that some characters have moved from the similarities that led to friendship in the beginning start to fill the movie with tension. You never know whose phone will ring, and what new information will be revealed.

Notifications are used as a ticking bomb in this movie, providing a sort of suspense that is hard to equate to anything other than a horror film. The difference between this movie and a horror film, though, is that you can’t shout at the screen “don’t go into that locked closet!” The characters commit their damning act early on in the film. Putting their phones on the table unleashes a plotline that takes a few elements from Greek tragedies: the second the devices are front and center, we know we will spend the rest of the movie watching our characters meet their demise.

What is interesting about this movie is that it is predicated on a very Italian (and European) form of friendship. These seven characters have been friends for life, and it can be seen in how comfortable they are in each other’s company. These people aren’t friends because of newfound adult common interests, or even because of college, they’re simply friends because they… always have been.

Long-term friendships like this don’t endure as commonly in the United States as they do in Italy. Americans are more likely to move out of their hometowns for work or other reasons, thus leaving behind the community in which they grew up. For the movie to work in an American context, it might need to feature a tight-knit nuclear family. Imagine you’re sitting at dinner, and your mom receives a text from her other child. A peaceful, enjoyable meal would probably be off the table (no pun intended). Secrets leap out of Pandora’s box in Perfetti Sconosciuti, and it’s only a matter of time before everyone’s dirty laundry is hung out to dry.

Watch it On Your Own!

Will these seven italiani stay friends? Watch for yourself to find out. Perfetti Sconosciuti is a roller-coaster of a film, and you strap in to the mayhem from the very beginning. Check it out to practice your Italian listening skills while considering how technology impacts your relationships. The movie is so great that there’s an American version starring Issa Rae on the horizon. But be sure to watch the original so that you can tell your friends “Oh, I saw the Italian version already,” and feel like a hip and international cinema-lover. Would you ever try this experiment at a friends’ dinner? What about with your family? Comment below, and be sure to give this blog a heart!

A Food Tour of Italy's Twenty Regions

There’s only one word to sum-up Italian food: variety

As we’ve mentioned before, Italian culture is not the same throughout the country. More often than not, it is defined on the town-level more than anything else. We unfortunately don’t have the resources to talk about the culinary variation of every single Italian paesino, so we’ll be walking you through a food tour of Italy’s regions instead.

Italy has twenty regions, all of which exercise a certain amount of political authority within their borders. Most of these regions have cultures dating back to before Italy was unified, and belonged to various empires and city-states over the course of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Regions like Veneto and Liguria were the home bases of maritime empires, while almost all of southern Italy was once part of the Kingdom of Two Sicilies. All of these political differences and slight variations in regional geographies mean that the culinary experience from one region to another can be quite different. Let’s check out some examples!

Northern Italy (Italia Settentrionale)

Piemonte

If you’ve ever heard of Fiat, you should know where Piemonte is. The region, including its largest city Torino, is a hotbed of Italian industry. Located in the northeast along the French-Italian border, Piemonte’s food culture is defined by a more buttery palate. To get a taste of this region, try eating some vitello tonnato. This dish takes surf and turf to a whole new level. It’s veal cutlets covered in a tuna-based sauce that infuses neighboring Ligurian capers and anchovies into a memorable meal.

Valle d’Aosta

This semi-francophone region is an Alpine wonderland. Try the zuppa della valpelline, which is a bread-based soup made with kale, fontina cheese, butter, and a sprinkle of cinnamon. The hearty soup will keep you warm as you endure the chilling temperatures while exploring the breathtaking landscape.

Trentino-Alto Adige

A region with a very Germanic past and present, Trentino-Alto Adige is a bilingual region on the Austrian border. A key dish here is the canederli di fegato, which are croquette-like dough balls cooked with seasonal vegetables.

Lombardia

Lombardia is in central Northern Italy. Home to fashion capital Milan, this region boasts the largest and wealthiest metropolitan area in Italy. To get a taste of what it has to offer, try yourself some risotto alla milanese. It’s made of beef stock, bone marrow, white wine, and parmesan. Its beautiful, signature yellow color comes from saffron.

Veneto

Veneto, in Italy’s northeast, has a bit of an independent streak. Once the site of the maritime Venetian Empire (and modern-day Venice, to boot), the cuisine of Veneto has been influenced by the myriad products bustling in and out of its seaport. Combined with the Austrian influence to the North and the inland cuisine to the west, Veneto’s cuisine is hard to pin down. In order to sample multiple Venetian flavors, order some cicchetti, which are little toasts topped with fish or meat. Enough of these will definitely constitute a meal, all while sampling as much as possible.

Friuli - Venezia Giulia

Friuli - Venezia Giulia’s name is a mouthful. Geographically, the region is positioned north of Veneto and nestled in between both mountains and the sea. Sample some bollito misto for a true taste of the region. It’s a platter of boiled meats that is made all over Northern Italy, but especially famous in Friuli - Venezia Giulia.

Liguria

Other than Genova and beautiful Cinque Terre, Liguria is famous for two things: pesto and focaccia. These two salty, oily treats can go hand-in-hand, or incorporated into other recipes. Pesto making is an art, and the fresh version beats its jarred counterpart every time. Focaccia is delicious at any time of day. Dunk it in your espresso or eat it alongside your dinner. Versatile and delicious, these Ligurian staples should be constantly stocked in your kitchen.

Emilia-Romagna

The southernmost northern Italian region, Emilia-Romagna is led by capital city Bologna, which boasts a large concentration of students. To get in touch with the region’s cuisine, you might be thinking about trying some spaghetti bolognese. To be more authentic about things, you’d be better off trying ragù alla bolognese. It’ll still be a classic bolognese sauce with beef, pork, carrots, celery, and some red wine, but instead of spaghetti, the sauce will be served on top of tagliatelle.

Central Italy (Italia Centrale)

Toscana

Tuscany, birthplace of the Standard Italian language that we all know, love, and study today. Tuscany is quintessential central Italy. Try some bistecca alla fiorentina, which is traditionally a piece of veal. You’ll probably have to travel to Florence to try an authentic version of the meal, since so much of it is about how the cow was raised (and cut). That being said, pair your grilled steak with some chianti and some of that classic unsalted Florentine bread for a taste of this iconic Italian region.

Umbria

Umbria is a tiny, landlocked region that’s known for its truffles. Try a frittata al tartufo (a truffle omelette) to get this delicious flavor in your breakfast (or dinner, if you’re trying to eat like a true Italian).

Marche

Marche is an Italian region with one iconic meal, vincisgrassi, which is a type of lasagna. The dish’s mythology centers around the celebration of Austrian general Alfred von Windisch-Graetz, who fought Napoleon in the name of Ancona. While the recipe is older than this story, the legend is now a key ingredient in its preparation.

Lazio

Lazio, home to Rome, is a region whose culture has stood the test of time. Even though Rome itself is cosmopolitan and international, its surrounding region holds onto a strong culture that has lasted centuries. Lazian cuisine features lots of pasta, artichokes, and pork. In addition to the carbonara, try eating some bucatini all’amatriciana.

Sardegna

A region unto itself, Sardina isn’t like the rest of Italy. Its cuisine is often highlighted by its Catalonian past, seasoned with lots of saffron. Try the aragosta alla catalana, Catalan-style lobster, with a side of risotto to get a taste of the cultural fusion happening on this island.

Southern Italy (Italia Meridionale)

Abruzzo

Abruzzo sits along the Adriatic sea, and is so far north that it is geographically sometimes considered central Italy. That being said, its culture and history ensure that it is almost always categorized as part of the south. In Abruzzo, be sure to try the agnello cacio e uova, which is roasted lamb egg, pepper, cheese, and prosciutto. The dish harks back on the region’s history as a land of sheepherders.

Molise

Molise, historically part of Abruzzo, is known for its use of pepperoncini, or spicy peppers. To experience this region’s spice, try some spaghetti diavolillo. It’s a simple spaghetti topped with a spicy red sauce that will have you reaching for some mozzarella to cool your taste buds.

Campania

Campania is where Naples is. A region fertilized by its nearby volcanoes, its population of flora includes eggplant, tomato, pepper, figs, and lemons. We’d be remiss not to recommend that you eat some pizza while you’re there. It’s the homeland of the modern pie, and the local buffalo mozzarella and San Marzano tomatoes will have you writing home that you’re never eating American pizza again.

Basilicata

Basilicata is a lesser-known Italian region, nestled between Calabria, Campania, and Puglia. Try the baccalà con i peperoni cruschi (salted cod with crushed bell peppers). The dish highlights both the region’s coastline and its vast fields of red bell peppers.

Puglia

Puglia comprises the “heel” of the Italian boot. Resting on the adriatic sea, the region boasts perfect Mediterranean weather for olive and grain growing. Try the tiella pugliese, which is a dish made of rice, potatoes, and mussels.

Calabria

Calabria, or the “toe” part of Italy’s boot, is another region with toasty climates and “warm-weather” cuisine. A unique dish to try from this region is involtini di pesce spada, or swordfish rolls. Breaded and flavored with red sauce, capers, olives, lemons, oregano, and parsley, they’re everything that makes southern Italian cuisine so delicious, all rolled up into one!

Sicilia

Ah, Sicily, the motherland for many Italian-Americans and the birthplace of many foods that Americans believe to be quintessentially “Italian.” Some foods, like cannoli, are hard to find north of the island, even in other southern regions like Naples. That being said, to get a taste of Sicily that you can’t get elsewhere, try eating some panelle, or chickpea fritters. Douse them in a healthy amount of parsley and lemon juice and have yourself a snack that is a staple of Palermo street-food.

Mangia!

That’s a lot of food to try. We believe in you (and your stomachs). Which Italian cuisine is your favorite? The more buttery and rich flavors of the north or the more Mediterranean flavors of the south? Comment below, and be sure to give this post a heart!

(Thumbnail photo by Cloris Ying)

The La Spezia-Rimini Line: Where Italian Varieties Collide

Where in the boot is your favorite dialect?

by Brian Alcamo

Two Italian families. Irreconcilable differences. Stop me before I start performing the entire plot of Romeo and Juliet. Epic theater aside, the set up for the iconic Shakespeare piece is also a good way to begin looking at the linguistic makeup of the Italian peninsula. Here’s what I mean.

Italian is a divided language. It is not a language defined by its country’s borders. The country’s culture is often described as campanilismo, which roughly translates to “a culture defined by bell towers.” This is to say that Italian culture and language can be highly fractured, all the way down to the neighborhood level. This is s the reason so many American travelers struggle to find a good cannolo north of Sicily. But it’s also part of the reason why Italy’s linguistic variation takes on a sharp divide a few miles north of Florence.

The La Spezia Rimini Line

A map of Italian dialects, with the La Spezia-Rimini Line in Black

The La Spezia-Rimini Line runs between the Italian towns of, you guessed it, La Spezia and Rimini. This line is an isogloss, which is a fancy word for a geographical boundary between linguistic features. The line is also sometimes referred to as the Massa-Senigallia Line, depending on whether or not the person wants to draw the line along traditional regional boundaries.

Languages north of the line exhibit features more similar to Western Romance languages (which include Spanish, French, and Catalan), while languages south of the line exhibit features more similar to Southern and Eastern Romance languages (Italian and Romanian, in particular).

Other less familiar languages that fall along these lines are Lombard, Venetian, and Piedmontese on the Western Romance side. Standard Italian, Neapolitan, and Roman fall on the Eastern Side. These languages can be divided further into two separate families, one being Gallo-Italic (North of the Line) and the other being Italo-Dalmatian (South of the Line).

This linguistic division is found in a few ways speakers pronounce words, with one of the largest distinctions being double consonants. Double consonants, or geminates, are a big part of standard Italian. They’re found in words like gemelli (twins), accademia (academy), and troppo (too much). Geminates can be kind of a pain for English-native Italian learners. They’re difficult to identify with the untrained ear, and are even harder to reproduce with an untrained mouth. If anyone ever comments on your mispronounced consonanti doppie, just tell them that your practicing your Lombard. North of the La Spezia-Rimini Line, these double consonants often become single. Other differences that you might pick up on north of this isogloss include: the dropping of word-final vowels (mano becomes man), forming plurals using the letter -s instead of changing the vowel, and pronouncing the letter c as an -s instead of a “ch” before the vowels i and e.

All of these differences are only present on the dialect level for the most part. Dialects are not the same as accents, so an Italian speaker from Milan will still form their plurals by changing a word’s final vowel. They’ll also most likely perfectly pronounce a double consonant if given the chance.

What Does This Mean For Italian?

As Italian standardizes and the world globalizes, these distinctions continue to erode. However, they provide a fun way to begin to think about the connection between geography and language. Italian is a young country, having only become a nation-state in 1861. There are still traces of its regional past everywhere. Although there won’t be any fanfare when you cross the La Spezia-Rimini line, be sure to pay more attention to the speech differences depending on where your conversation partner is from. In addition to practicing your listening skills, you’ll be sure to feel like a linguistic detective.

Thanks For Reading!

Where’s your favorite Italian speaker from? Do you think their dialect might be a little different from “textbook” Italian? Comment below, and be sure to give this post a heart!

(Thumbnail photo by Dominik Dancs)

Computers Appreciate Art, Too: Italian Technology Preserves Artistic Artifacts

Want to restore your favorite painting? Come to Venice.

by Brian Alcamo

Italy’s arrival to the world of high tech took a little more time than other countries in the European Union. You could blame the tardiness on a laid-back Mediterranean lifestyle, but Spain’s tech boom would have you begging to differ. More likely, Italy’s startup scene has been slow-growing due to a lack of funding (which prevented the fledgling companies from scaling). It’s not only startups that have grown slowly, though. The culture surrounding digital life is taking a while to flesh out, as well. Even in recent years, the country has been “starting from scratch” in its attempt to build out its digital footprint, with only 10% of businesses selling their services online. Back in 2016, the country was lagging behind the rest of Europe. Thankfully in recent years, startups have been receiving more money, and Italy is ready to carve out a space for itself in Europe’s growing tech industry.

A Decentralized Center for Scientific Research

Serving as an academic backbone for the technological innovation taking place all over the Italian peninsula is the Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia (IIT). Based in Genoa, this scientific research center has 11 partner locations all over Italy, and 2 other partnerships with MIT and Harvard.

A blog post from MIT’s Technology Review boasts that Italy still has a very active manufacturing economy that relies on nimble networks of small and mid-sized companies rather than larger monopolies. In fact, Italy is so ready to ride on its industrial prowess that it launched Industry 4.0 back in 2016. The initiative is in collaboration with Germany and France to promote digital standards of manufacturing.

While Italy might be playing catch up when it comes to promoting digital methods of work and connectivity, it was a center of innovation during a few periods of history (just tiny things, though, like Ancient Rome and the Renaissance). Merging its older troves of artifacts while embracing modern methods that will help the country succeed in the future.

Cultural Heritage Technologies Bridge the Gap Between Old and New

Cultural Heritage Technology has a huge presence in Venice, but is also making a name for itself in Rome. (Livia Hengel)

One particularly novel approach coming out of multidisciplinary efforts are Cultural Heritage Technologies. Cultural Heritage Technologies are the exact kind of technology that you’d expect to be flourishing in Italy. These technologies work to combine modern computing and machinery with the complex pieces of heritage, both tactile and esoteric, that make human culture so captivating to study and experience. Arianna Traviglia is the Coordinator of the IIT Centre for Cultural Heritage Technology. Her work is based at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, which offers a Masters Degree in Conservation Science and Technology for Cultural Heritage. Think of it as the 2020 equivalent of whatever Armie Hammer’s character was studying in Call Me By Your Name. The same amount of sculptures and statues, just more computers and coding.

The discipline combines aspects of art history, computer science, life sciences, humanities, and even robotics. The technology hopes to be used in restoring and digitizing the sometimes fragile artifacts of past civilizations. Here’s a link to a paper discussing machine learning in cultural heritage work if you’re looking to geek out. Many Italians are hopeful that digital technologies will help preserve and propagate their history. What better place to cultivate the science of cultural preservation than in a country with 50 UNESCO Cultural Heritage sites?

In a 2018 interview with Ca’ Foscari University’s news outlet, program coordinator Elisabetta Zendri describes some of the department’s projects, such as The Tintoretto project, which is a collaborative effort that aims to study “the ceiling teleri in the Chapter House of the Scuola [Scuola Grande San Rocco] and,” and analyzes “the influence of the environment on the stability of these extraordinary works.” She believes that material conservation will be a big part of the future. However, while high tech restorative efforts make the headlines most often, the culture of conservation much “switch from the concept of ‘restoration’ to the ones of ‘prevention’ and ‘maintenance.’”

A Bright Future

Italy may have been late to the high tech game, but it’s well on its way to standing with the rest of the world in terms of technological advancement. Just look at recent headlines for its contact tracing app, or Europe’s weather center’s move from London to Bologna. The country is even building an app that centralizes government documents and bills. In the meantime, we can dream of a future filled with robots that look like Renaissance statues.

Thanks for Reading!

Would you have your favorite painting restored with the help of a robot? Comment below, and be sure to share this post with your friends.

(Thumbnail Photo by Marco Secchi)

"What's a muzzadell?" Exploring Italian American Food Vocabulary

Have you ever wondered why the Italian at your deli is different from the Italian in your textbook?

by Brian Alcamo

Let me describe to you a feeling that anyone who appreciates Italian culture has felt.

A few times, my grandpa has brought over “banellis”, a fried chickpea pancake of sorts. They’re delicious, and can be dressed up in a multitude of savory flavorings (or sweet, if you’re looking to go against your nonna’s traditions). They’re the kind of treat that’s hearty enough to trick yourself into thinking they’re healthy.

This summer, my grandpa once again brought us some “banellis” from his favorite deli in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, and I was reminded of how delicious they were. After having bought upwards of 10 pounds of chickpeas at the beginning of quarantine out of fear of not being able to go to the grocery store, I wanted to try to make “benellis” on my own.

Naturally, I went to Google. It turns out that “banelli” is the name of a rifle company, not a dense Italian pastry. I searched for “banelli chickpea” and had to scroll a bit before I could find what I was looking for: Panelle. It turns out that panelle (singular: panella) are “chickpea fritters,” and are a popular street food in Palermo, the capital and largest city in Sicily. The word is pronounced in Italian as [panelle]. Happy with my successful search, I still felt the unwelcome sentiment of being an uncultured American(o). Why can’t I just be from Italy? Why is this panelle so different from how my grandpa and other Italian Americans pronounce the word [bəneli]? The answer lies in which Italians came to America, and how their dialects differ from standard Italian.

A Brief History of Italian In the US

From the late 19th to the mid 20th century, the US saw huge numbers of Italians arriving to escape poverty, stake their claim, and try to live out the American dream. Many of these Italians came from Southern Italy and Sicily, bringing with them their non-standard regional varieties of Italian. Standard Italian was derived from the Florentine dialect of central Italy, thus the sounds and vocabulary shipping over to the US were slightly (sometimes drastically) different. For example, Sicilian is considered by many to even be a separate language. In addition to Latin, it has myriad other influences due to its changes in ruling class over the centuries. Some of these influences include Greek, Arabic, French, Catalan, and Spanish. Sicilian isn’t even the only Southern dialect, and many others such as Neapolitan and Calabrese found their way to the US as well.

All of these tiny linguistic differences combined with the influence of American English create a perfect recipe for vast differences in pronunciation across the Atlantic. Unfortunately, these differences were not always viewed with prestige. James Pasto, in his paper “Goombish” says that “Southern Italians came to the United States speaking already stigmatized dialects, developing a short-lived hybrid, Italgish, that was also stigmatized by speakers of both standardized English and Italian.”

Differences Between Italian American and Standard Italian Words

In order to discuss the differences between Italian American and Standard Italian Words, we must start by acknowledging that Italian American words typically come from a Southern Italian dialect. We’re only going to look at a few examples here, but if you want a better overview, start by checking out this blog post over on Mango Languages. To keep things simple, let’s use some vocabulary that we all know and love, food. Food is integral to Italian American culture, and is a major way in which the Italian language lives on in the US. NJ.com even has an article about “How to speak Jersey restaurant Italian.”

(Keep in mind that each person may pronounce these words differently. Even different families in the same community may have slight variations in their pronunciations. These are not strict rules, and should be used as simple guides to help you reconstruct the Standard Italian pronunciation and spelling.)

Take a look at these Italian American words coupled with their standard counterparts:

Brosciutt’ : prosciutto

Gabagool : capacolla

Fajool (think “pasta fajool”) : faggiole

Rigott’ : ricotta

Muzzarell’/muzzadell’ : mozzarella

Ganol’ : cannoli

Mortadell’ : mortadella

Sound Changes

A lot of these pronunciations come from how speakers of Southern dialects pronounce words.

What’s often happening in these differences is that the Italian American version contains the voiced version of many unvoiced Italian consonants. A voiced consonant is a consonant in which your vocal folds (commonly referred to vocal chords) vibrate while you pronounce it.

Take for instance “k” versus “g.” K is unvoiced whereas g is voiced. The process of changing an unvoiced consonant to its voiced counterpart is known as voicing. Voicing happens three times in the example of capocollo (a type of cured pork) turning into gabagool.

There are also many words that get rid of the final vowel: prosciutto becomes brosciutt’.

A Note on Plurals

When discussing Italian food items in the US, people often use the plural noun form to describe a singular quantity of something. In Italian, one cookie is un biscotto, but in English, one crunchy, Italian-style cookie is “a biscotti.” To form the plural in English, you simply add an -s to the end of the once-plural-but-now-singular biscotti. The same holds true for panini, panelle, and cannoli (singular panino, panella, and cannolo, respectively).

Here’s the rule: If the name of your favorite Italian food ends in an -i, it’s singular form will either be an -o or an -e. If the word ends in an -e, it might already be singular, or it will have a singular form that ends in an -a.

Trying it Out on Your Own

Learning Italian is a lifelong process for many. It’s a way that many try to reconnect with their Italian heritage, and to move their vocabulary beyond the names of food and slang terms (I’m looking at you, stunad (stonato)). Try delving into a specific dialect on your own once you’re comfortable enough with your congiuntivo passato prossimo and your consonanti doppie. You won’t regret it. At the very least, you’ll be even more appreciative on your next trip to the deli.

(Thumbnail photo by Jez Timms on Unsplash)

How to Make an Easy and Authentic Italian Risotto

Learn to cook a simple risotto, an Italian favorite!

by Brian Alcamo

Like many of the creamier Italian dishes, risotto’s history resides in the north of Italy. Rice’s life in Italy began in the 14th century CE, during the Middle Ages when Sicily was being ruled by the Arabic caliphate. It was particularly the short-grained rice that fared the best in the Mediterranean climate of Italy. To this day, a true risotto can only be made from an Italian short-grain rice type (like arborio or carnaroli).

The word risotto consists of two parts riso and -otto. Riso is Italian for the word “rice.” The suffix otto can be used to form pejoratives and it can be an alternative to the suffix etto, which is used to form diminutives. While the otto in risotto is fairly idiomatic at this point in the word’s history, it might come from the pejorative sense, being that risotto is cooked for so long that its consistency is something entirely different from typically cooked rice.

Missed our IG Live collab with Time Out New York where we make this delicious recipe? No problem! Find it below on IGTV.

The Recipe:

(For 4 people) A simple, classic risotto, perfect as a base, vegetarian

Ingredients

400g of Rice (Arborio, Carnaroli or Vialone Nano)

1 White Onion, finely chopped

Half a glass of dry white wine

1L of Vegetable or Beef broth (Seasoned with salt, no extra salt will go in this recipe)

A bit of Butter Olive Oil qb ( quanto basta)

100g of Parmigiano Reggiano finely grated Sea salt.

Freshly ground black pepper (a piacere)

Procedure

1.Finely chop the onion

2. keep the broth hot (previously prepared)

3. Gently heat the extra virgin olive oil in a medium straight sided pan. You can add a little piece of butter if you prefer. Add the onions finely chopped, and cook until fragrant and beginning to soften, just a couple of minutes.

4. Add the rice and stir until every grain is coated with the oil. Keep at medium heat and continue stirring the rice until the edges have turned translucent, but the center is still opaque, about 2/ 3 minutes.

5. Once the rice is well toasted, add half of dry white wine glass and let the wine evaporate while continuing stirring constantly. Add a little broth, mix well and bring it to a low heat.

6. Slowly add the broth and increments stirring in between. ½ cup or so at time. Wait until the liquid has been almost completely absorbed by the rice before adding the next ladle.

7. Continue adding broth until the rice is al dente and the broth is creamy, risotto shouldn’t be sticky, but it should be fluid like a wave gentle running the shore. It has to be creamy silkiness

8. Once the rice is al dente, shut the flame off and start to mantecare.

9. Grate the Parmigiano Reggiano and add a bit of butter and with the help of a wooden spoon mix energetically. Then cover for a couple of minutes.

10. Serve in a flat plate and tap it down to spread evenly.

11. Enjoy it!

Let’s Practice your Italian!

Now that you made your dish, let’s review some Italian vocab so you can buff up your language skills!

Tagliare= to cut

Tritare= to minced / to chop up

Cuocere= to cook

Rosolare= to brown

Tostare= to toast

Mescolare= to stir

Aggiungere= to add

Spegnere il fuoco= to shut the flame off

Grattuggiare= to grate

Mantecare= whisk

Cipolla= onion

Burro= butter

Olio= oil

Riso= rice

Brodo= broth

Sale= salt

Pepe= pepper

Bicchiere di vino bianco= glass of white wine

That’s all there is to it! Be sure to share this recipe with your friends and comment below how it turned out for you! A presto!

(Thumbnail photo by Julien Pianetti on Unsplash)

Wellness Tips in Italiano

Learn Italian while taking care of your physical and emotional well-being.

by Brian Alcamo

Oddio! These past few weeks have been shocking to everyone. Thanks to a certain virus, many of us are stuck at home trying to flatten a certain curve. Staying home might not seem conducive to practicing a language or maintaining your well-being, but we promise it is. Learning Italian, or any language, is one of the best ways to stay sharp and give your brain a workout. But what about your body and soul? Try combining a linguistic challenge with some exercise or a mindfulness practice to spice up your language learning and your pursuit of wellness. Here are some of our favorite online resources to get you started!

Physical Wellbeing takes a two-pronged approach. The first is healthy eating, which is a topic so large that we don’t have the time to cover it in this post (keep your eyes on the JP Linguistics blog for that one!) The second is exercise.

Exercise: If you’re looking for a workout video in Italian, you’re in luck! It turns out that Italians exercise just like you and me, and they have the twenty minute Zumba promotional trial workout to prove it. There’s also FixFit, a mobile application and YouTube channel with over 1,000 workout tutorials to choose from. If Instagram is more your speed, feel free to give Paolo Fontana a follow. He’s a trainer at Barry’s Milan, and has an Instagram Story Highlight called “Quarantine 🔥” with an at home workout in Italian. Train your glutes and your imperative conjugations tutti insieme!

Here are a few vocabulary words to get you started.

Allenamento = workout

Riscaldamento = warm up

Rilassarsi = to cool down

Sudare = to sweat

Allungare = to stretch

Emotional Wellbeing: One of my favorite techniques to better my emotional wellbeing is a good ole mindfulness meditation practice. Popularized by apps like Calm and Headspace, this is a great way to learn how to work with the ebbs and flows of your personal emotional tapestry, during or not during a global pandemic.

If you want to learn a little bit more about meditation in general, check out YouTuber’s Marcello Ascani’s meditation journey, or Alice LifeStyle’s “Iniziare a Meditare”, (and her comprehensive accompanying blog post, for people who prefer to read their Italian). In addition, here’s Dr. Filippo Ongaro's take on why meditation is fundamental to personal growth. His channel is filled with videos that span the spectrum of wellness education, so check it out for other types of content not related to meditation.

Here are some important words to get your meditazione italiana up and running down and sitting.

meditazione guidata - guided meditation

inspirare* = to breathe in

espirare* = to breathe out

respiro* = (n. m) breath

lasciare = to let (since you’ll be letting a lot of thoughts drift away!)

*Lingo Lookout: You’ll notice the root “spir” in a lot of words that have to do with meditation. That’s because “spir” is the Latin root for “breath,” and meditation is all about the breath. In English, you can find the root in words such as “spirit,” “conspire,” and “aspire.”

The internet is filled to the brim with videos geared towards helping you get and stay as fit as you can be. Coupled with the allenamento mentale of practicing your Italian listening skills will help keep you motivated educationally and energetically. We at JP Linguistics also want to take the time to send love to everyone who’s battling the coronavirus, and say a big grazie mille to healthcare professionals across the globe.

Practice these words with our quizlet set.

(Thumbnail Photo by Jared Rice on Unsplash)

How To Make Tiramisu - A Simple & Delicious Recipe

Is it a pudding? Is it an Italian cake? Whatever it is, it’s delicious.

by Brian Alcamo

Ti-ra-mi-su. Four syllables. Six ingredients (on average). The iconic Italian dessert holds a special place in the hearts of many people. It’s a perfectly light treat for the end of a meal, and goes great with an espresso and some post-meal conversation. When you read a recipe for tiramisu, the list of ingredients doesn’t necessarily help to convey what the end result will taste like. For this reason, some have described it as having a “mutant flavor”. One ingredient you won’t need? Liquor. While the flavor might be mutant, that’s exactly why we like it.

Origins of Tiramisu

Tiramisu, like many other cultural staples, has a contested point of origin. While the sources of its beginnings are not as far as salsa’s, they are not entirely agreed upon. The narrowest point of origin that people can agree upon is Italia settentrionale, or Northern Italy. The regions where it most likely came from are Veneto, Friulia Venezia Giulia, or Piemonte.

(the regions Piemonte, Veneto, and Friulia Venezia Giulia are part of the larger Northern Italy)

A Sentence with No Spaces

The origin of the word tiramisu comes from a strung-together Italian sentence. Tirami su.

Tirare means to toss or throw, mi is the direct object pronoun “me,” and su means above or over. Tirare is conjugated in the imperative mood, which allows the speaker to place the direct object pronoun after the verb instead of before it.

The whole sentence (and now word) translates to “Pick me up,” which might have to do with the caffeine content of a key ingredient.

Originally, though, the word wasn’t Italian at all. At least, not the Standard Italian that many of us at JP Linguistics know, love, and study. Many people credit its beginnings to the city of Treviso in Veneto, a region in Northern Italy (Venice’s region). In the Treviso regional language the word was “tireme su.”

Our Simple Tiramisu Recipe

Didn’t get a chance to tune into our Live Workshop with TimeIn New York? That’s okay. We’ve got our recipe right here (certo in inglese e in italiano).

Ingredienti per 4-6 persone (Ingredients for 4-6 people)

4 uova intere (4 whole eggs)

300 gr. di zucchero bianco (1.5 c of white sugar)

500 gr. di mascarpone (2.5 c of mascarpone)

40/45 biscotti savoiardi (40/45 ladyfingers)

300 cc. di caffè amaro e forte lasciato raffreddare (1 ¼ c of chilled, strongly brewed coffee)

100 gr. di spolvero di cacao amaro (½ c of dark chocolate powder)

Procedimento (Instructions)

Preparare preventivamente il caffè e lasciarlo raffreddare.

Prepare the coffee beforehand and let it cool.

Porre in una terrina 3 albumi di uovo e montarli a neve con un pizzico di sale.

Place 3 egg whites in a bowl and beat them stiff with a pinch of salt.

Con una frusta sbattere i 3 tuorli e l’uovo intero assieme allo zucchero quindi, aiutandosi con una spatola, aggiungere il mascarpone e mescolare piano piano dal basso verso l’alto fino a formare una crema.

With a whisk, beat the 3 egg yolks and the whole egg together with the sugar then, with the help of a spatula, add the mascarpone cheese and stir slowly from bottom to top until it forms a cream.

Infine aggiungere gli albumi montati a neve e amalgamare il tutto mescolando sempre molto piano, dal basso verso l’alto, per non smontare la crema.

Finally add the egg whites whipped to stiff peaks and mix everything, stirring always very slowly, from the bottom to the top, so as not to dismantle the cream.

Sul fondo piatto di una terrina o di una pirofila adagiare uno strato di savoiardi, inzuppati nel caffè, sgocciolati e leggermente spremuti con una forchetta per eliminare il liquido in eccesso.

On the flat bottom of a bowl or an ovenproof dish lay a layer of ladyfingers, soaked in coffee, drained and lightly squeezed with a fork to eliminate the excess liquid.

Sullo strato di savoiardi stendere uno strato pari alla metà della crema preparata.

On the layer of ladyfingers spread a layer equal to half of the prepared cream.

Quindi stendere sopra di essa un secondo strato di savoiardi, inzuppati e trattati come i precedenti.

Then spread a second layer of ladyfingers on top of it, soaked and treated like the previous ones.

Spalmare sopra la rimanente crema.

Spread the remaining cream on top.

Riporre il dolce in frigorifero per 12 ore e gustarlo dopo averlo spolverato con il cacao amaro aiutandosi con un colino.

Place the dessert in the refrigerator for 12 hours and enjoy it after sprinkling it with bitter cocoa using a sieve.

That’s all there is too it! Only a few ingredients, but a lot of "wrist work” (whisking, whipping, and sprinkling) and a lot of waiting will get you that delicious flavor that only comes from a properly made tiramisu. Now all you need is the limoncelo…

Grazie!

Make sure you give this blog a heart, and share it with your friends. Tried the recipe? Let us know how it turned out in the comments section.

(Thumbnail Photo by Vika Aleksandrova on Unsplash)

How To Make Crispeddi Cu Brocculu (Cauliflower Fritters)

There are so many more daily cuisine options from Italy than what you may already know…

When most Americans think of Italian cuisine, the idea of family-style pasta dishes set around a dinner table come to mind. While this scene is born mostly from our stereotype of Italian-American migrant families in the early 1900s, there is so much more to the daily cuisine options from Italy. One of the lesser known comes from Southern Italy called crispeddi cu brocculu.

Photo: Mangia Bedda

Crispeddi Cu Brocculu Recipe

This street-style favorite is sure to become a favorite as either a starter for your next family meal or as a side dish to the main course. We’ve dropped our favorite variation on the recipe courtesy of Mangia Bedda.

First, You’ll Need These Ingredients:

1 small cauliflower head about 3 cups

2 large eggs

1 cup all-purpose flour

1/2 tsp baking powder

3/4 cup water

1 tsp salt

vegetable or canola oil for frying

Photo: Mangia Bedda

How to Prepare

Separate the cauliflower into bite size florets and boil in salted water until tender, about 8 minutes. Drain, and set aside.

In a large bowl, beat the eggs. Add the water, flour, baking powder, and salt and stir until well combined. You are looking for the consistency of a pancake batter. Stir in the cauliflower chunks and toss to coat in the batter.

Cover the bottom of a large, wide skillet with enough oil to reach the depth of 1 cm (about 1/2 inch). When the oil is hot, drop heaping spoonfuls of batter into the pan. I fry six crispeddi at a time. You can place them close together as they will not stick together.

Fry until golden and crisp, about 3 minutes per side. Transfer to a plate covered in paper towels to soak up excess oil.

Serve hot.

These fritters are best eaten hot right out of the pan. However, if you have leftovers you can enjoy the next day by warming them in a 350F oven for about ten minutes. They will crisp up again.

Photo: Mangia Bedda

We hope you’ve enjoyed learning about how to make How To Make Crispeddi Cu Brocculu! Itching to try this delectable treat in it’s home country? Our native instructors and culturally immersive group courses will ensure that getting your order in is facile! Click below to learn more.

Italian Culture - A Guide for Visitors

Thinking of making a trip to Italy, but don’t want to be the typical tourist?

Thinking of making a trip to Italy, but don’t want to be the typical ignorant tourist? Perhaps you’re wishing to be able to take in all of the sights and sounds to their fullest extent? While it’s obvious that becoming proficient in the language is the easiest way to improve your trip, having some insight into the overall history of the country will aid you in appreciating every site you plan to visit!

Language

The official language of the country is, you guessed it, Italian. About 90% of the country’s population speaks Italian as native language with many dialects including Sardinian, Friulian, Neapolitan, Sicilian, Ligurian, Piedmontese, Venetian, Calabrian, and Milanese. Other languages spoken by native Italians include Albanian, Bavarian, Catalan, Cimbrian, Corsican, Croatian, French, German, Greek, Slovenian and Walser.

Family and Religion

Family is an extremely important value within the Italian culture and family solidarity is focused on extended family rather than the immediate family of just a mom, dad and children. Most families in Italy also happen to be very religious with the major religion in Italy being Roman Catholicism. This seems pretty obvious considering that Vatican City is the hub of Roman Catholicism.

Roman Catholics and other Christians make up 80% of the population while Muslim, agnostic and atheist make up the other 20% according to the Central Intelligence Agency.

Art and Architecture

Italy is home to many classic architectural styles, including classical Roman, Renaissance, Baroque and Neoclassical and is home to some of the most famous structures in the world, including the Colosseum and the Leaning Tower of Pisa to name a few. The concept of a basilica — which was originally used to describe an open public court building and evolved to mean a Catholic pilgrimage site was born in Italy.

Additionally, Opera has its roots in Italy and many famous operas including "Aida" and "La Traviata," and "Pagliacci" which are still performed in the native language to this day. In the world of fashion, Italy is home to some of the most famous fashion houses, including Armani, Gucci, Benetton, Versace and Prada to name a few.

Cuisine

Italian cuisine has influenced food culture around the world and is viewed as a form of art by many. Wine, cheese and pasta are important part of Italian meals. Pasta comes in a wide range of shapes, widths and lengths, including penne, spaghetti, linguine, fusilli and lasagna.

Wine is also a big part of Italian culture, and the country is home to some of the world's most famous vineyards., and in fact, the oldest traces of Italian wine were recently discovered in a cave near Sicily's southwest coast. Wine is produced in every region and is home to some of the oldest wine-producing regions in the world. Currently, Italy is the world's largest producer of wine.

We hope you’ve enjoyed our Italian Culture - A Guide for Visitors! What aspects of Italian culture would you like to learn more about? Join the conversation below!

Italian Dialect Or Language

Interestingly enough, Italian dialects are not truly dialects…

The Italian language is the only official language of Italy. Until 1861, however, Italy was a loose network of small states with each having own language. One of the unifying forces at the time was the Roman Catholic Church, and this year the Sa die da Sardigna (the Sardinian National Day) Mass, was celebrated in the “limba” dialect, a variant of the Sardinian language.

While the history behind the official usage of Italian is a long one, essentially, when the Savoy Kingdom unified all these states under its crown, the decision was made that the literary Florentine variant of Italian would become standard across the country. A major factor in this decision was that Florentine literature (Dante, Petrarca and Boccaccio to name a few) was read widely throughout Italy, and therefore was considered part of the national identity.

The newly standard language was taught in schools as part of a federal schooling program that made the instruction mandatory everywhere, however the usage of regional languages persisted and remain an integral part of Italy’s regional cultures.

Interestingly enough, Italian dialects are not truly dialects as a dialect is a variant of a codified language and many of these “dialects” developed independently with their own grammar and vocabularies. This would technically classify them as their own languages. Currently, there are 32 minority languages, all of them derived from the Latin.

For more info on each of the minority languages, click here!

We hope you've enjoyed learning about what denotes Dialect or Language in Italian! Ready to delve more into not only the Italian language, but the culture that it was born of? Our culturally infused group classes with native instructors are sure to put you on the path to fluency faster than you may think possible. Click below to learn more!

5 Phrases You Need to Know If You’re Spending Time in Italy This Holiday Season