Le Carrefour: Connecting French-Speaking Populations in Vacationland

Jessamine Irwin chats with us about Francophone immigrant experiences in Maine.

Jessamine Irwin, French professor and director of Le Carrefour

by Brian Alcamo

“Nobody knows about French in Maine, and nobody knows about all of the newcomers that have been arriving in the past few years,” Jessamine Irwin tells me over a Friday morning Zoom call. “It’s a lot of new information in thirty-two minutes.”

I recently sat down with French professor-turned-documentarian Jessamine Irwin to learn more about her first film, Le Carrefour (The Intersection). Why is it called the Intersection? The film explores “the intersection of francophone immigrant experiences in Maine.” The immigrant experiences which Ms. Irwin is referring to are those of white, older French speaking Mainers and those younger black French speaking population that has been steadily arriving since the mid 2010s. The film’s goal, she says, is to “serve as a catalyst to create a space for conversation surrounding immigration.” Some of these conversations, she hopes, will happen in French classrooms.

Jessamine, first and foremost, is a French educator. She cares about the plus-que-parfait, proper pronunciation of the French “R,” and pain au chocolat. While university French departments and other institutions that offer French classes consistently advertise French as a global language with over 250 million speakers, (making it the fifth most spoken language in the world!) courses typically only offer linguistic and cultural insights into one country: France.

Maine may not be the first place on the list of “French-speaking places that aren’t France” (you may be more inclined to think of Louisiana for that), but the East-Coast’s northernmost state has historically been a stronghold of the French language in the USA. Le Carrefour not only gives us insight into the present day immigrant experience in Maine, but also takes us through the history of immigration in French, answering many people’s (including protagonist Trésor’s) big question: why is there French in Maine to begin with?

Tresor, one of the film’s main subjects.

Cécile, another main focus of the film.

The journey of French into Maine began with the migration of Acadians into the state during Le Grand Derangement. This period of time, known as “The Great Upheaval,” in the mid 1700s, was an ethnic cleansing attempt imposed by the British after they took control of New France (present day Canada). Acadians lived off the land and worked with the woods, producing commodities like maple syrup and snowshoes. To this day, many of them are very tied to the forest. Acadian settlements in Maine are positioned extremely close to the Canadian/American border. Some of their relatives moved down south to Louisiana, particularly New Orleans. Their southern eponym slowly underwent a linguistic metamorphosis to become a word (and cuisine) we all know and love today, Cajun.

Back up north, though, a wide-reaching underground French speaking population has been living there since the dawn of the United States, and Jessamine Irwin wants you to know about it. Le Carrefour stars Tresor and Cecile. Tresor came to the USA from the Democratic Republic of Congo, with a pitstop in Brazil. He speaks French, Portuguese, Lingala, Tshiluba, and some English. He is well educated, having studied pedagogy in his home country and Performing Arts in Brazil. Beyond his official education, though, Tresor is also filled with more worldly knowledge than most people. Before coming to the US, he lived in Brazil. He says that moving to another country is “like being born again.” Logistically speaking, this unfortunately meant that Tresor’s degrees and work experience abroad aren’t recognized in the USA. Despite being highly educated, he works night shifts in a warehouse in Maine. Hardship like this, including having to learn new languages, adapt to a new environment and bureaucracy, and deal with the trauma that comes with displacement, is a common thread among immigrants and history, Jessamine says, repeats itself.

This repetition, she says, is playing out right now in Maine, tucked away in the far northeast corner of the country. Cécile, the film’s other protagonist, is aware of this past immigrant experience. She is part of Maine’s large Franco-American community, and there was a lot of shame in Cecile's generation for identifying as such. “Many people might understand Franco-American as an American who speaks French,” Jessamine specifies, “but in New England the term takes on a more specific definition.” Not to be confused with Acadians who moved to Maine before the mills, Franco-Americans are of French Canadian descent, either an immigrant themselves or a descendant of an immigrant who moved to Maine from Canada to work in the mills during the Industrial Revolution between the 1850s and the 1930s. Cécile and others faced intense shaming from the English-speaking public, and were discouraged from speaking their language and from worshipping Catholically. Franco-Americans were even targeted by one of the largest KKK chapters in the US. “If we avoid trying to make people feel like they’re ‘Not American Enough’ we can all benefit from the diversity, more easily learn from each other, give people a voice, give power to people, and break the generational cycle of assimilation trauma.”

A bridge in the middle of Lewiston, ME

Mainers are very aware of people who did not grow up in Maine. They even have a phrase for it: “coming from away.” “To me,” Jessamine explains, “‘Coming from away’ is a very nonmalicious way that Mainers describe outsiders. People care about the lived experiences of others. “Maine,” she continues, “is not ethnically diverse. It’s very white, with those white people typically having Irish and/or French Canadian heritage.” There’s certainly lots of racism to deal with in the state. This racism follows economic lines and gets more rampant up north, away from Portland, Maine’s largest city (of 67,000 people). “People want to find someone to blame for their own hardship.”

Some people in Maine are welcoming the newcomers with open arms. In 2019 with the first big wave of asylum seekers, the former mayor of Portland, turned the Expo Center into makeshift housing, welcoming the asylum seekers and making them feel like they belonged, helping them to not feel othered. “It’s dangerous to not make people feel welcome,” Jessamine says. “There’s been displacement forever, and most Americans are lucky to have not experienced it.” Maine has an aging population. Like the countries where the immigrants are coming from, the state is undergoing its own Brain Drain. However, Jessamine says, “it’s practically being gifted these super capable young people, and even has some of the linguistic infrastructure required to welcome these newcomers.” Jessamine and Tresor want people to understand that educated people are coming. Trésor believes that all these immigrants want to do is pursue their passions and move forward with the people of Maine. In the 1970s, there were 147,000 French speakers living in the state, and that number has dwindled since. Newcomers are not only breathing new life into Maine’s economy, but its French-speaking population as well. But not even all Mainers know about their own state’s Francophone backbone.

The Gendron Franco Center, a historic stronghold of Francophone culture in Maine

Jessamine, luckily, grew up aware of all of the French being spoken betwixt and between Maine’s maple trees. Jessamine’s mother grew up in Madawaska, a town right on the border of Canada’s French-speaking province of New Brunswick. Her mom grew up hearing French on the playground everyday at school, and this exposure led to her pursuit of French, which she studied at the University of Maine in Orono and turned into a career while working at the school’s Franco-American Center. Perhaps interest in the French language is passed down matrilineally, because Jessamine followed in her mother’s footsteps, beginning her formal French studies in high school.

Unfortunately, the filmmaker didn’t get to formally learn about the French speakers in her home state that she knew existed during those early years of apprentissage. “In my French classes before the university level, I never came into contact with Franco-American representations.” With the exception of one Canadian teacher who provided some insight into Canadian French and cultural traditions, most of her school books were Euro-centric.

Jessamine finally began to learn about the French language in her neck of the (literal) woods when she began studying at the University of Maine, her mom’s alma mater. Learning French, or any foreign language for that matter, tends to unlock opportunities, and Jessamine was able to study abroad in France during her time in college. “When I went to Paris for the first time, it was like my eyes opened,” she says. “People had no clue what Maine was, and made fun of North American French. At first, I kind of embraced it.” Due to societal pressures, Mrs. Irwin was embracing was the homogenous view that many French students and educators have of the French language and culture. Through her film, she wants to challenge those ideas and provide a resource to help bring the diversity of the French speaking world into the classroom.

Vocabulary For Your Next Discussion About Immigration En Français

Les frontières - Borders

L’identité culturelle - Cultural identity

Locuteur natif - Native speaker

La barrière de la langue - Language barrier

Une dictature - A dictatorship

Lewiston, the center of Maine’s Franco American population, is what many Mainers would describe as a “die hard mill-town,” a working class town filled with Franco Americans. It was founded at the beginning of the industrial revolution, and many immigrants from Quebec fondly remember taking the train down to the Grand Trunk Railroad station. The town features remnants of “Little Canada,” which used to be tenement housing built in rapid succession for the mill workers who were moving in droves. “The main street is easily identifiable, with the Continental Mill coming, then Little Canada, and then the Franco Center,” Jessamine says. In a course that she created at NYU, Jessamine creates that experience for her students on a week-long trip to the french-speaking parts of Maine. But in a less curated setting during her summer of shooting footage in Maine, Jessamine could still speak French every day.

Shooting with a bilingual team provided a few language-barrier challenges. Cecile is fully bilingual, Tresor is still working on his English. Jessamine’s co-director, Daniel Quintanilla could understand French, which helped for some on-set shooting snafus, since most of the film is in French and only two team members could decide whether enough footage was shot. Where her teammate’s knowledge of French was even more crucial, Jessamine said, was during the editing process. It turns out that screens and keyboards provide none of the social cues or body language to supplement spoken word.

If you’re wondering whether you can strike up a conversation in French with someone, the short answer is “yes.” Walking around Lewiston on a busy day (when it’s not freezing cold out), you can hear French in parks, spoken between friends and families old and young. You’re not considered a nuisance for trying to speak French, either. It’s a very “Maine” thing to acknowledge a passerby on the street. To wrap up our discussion, Jessamine recounted the story of when Cecile was asked “How can we be more welcoming to immigrants?” at a recent screening Q and A. Smiling, Jessamine recalled that Cecile advised people to simply “look people in the eyes and say ‘bonjour.’”

Thanks For Reading!

Interested in watching Le Carrefour? Head to their website and sign up for their newsletter to hear more about future opportunities to view the film.

Nostradamus And His French Astrological Legacy

Who was this notorious star-loving soothsayer?

by Brian Alcamo

Astrology has been seeing a huge revival in the past few years, in France as well as in the US. It seems like more people than ever know about not just their singes solaires (Sun Signs), but also their signes d’ascendant (Rising Signs/Ascendant Signs) and their signes lunaires (Moon Signs). It turns out that France is home to one of the West’s most famous astrologers, Nostradamus. Read on to learn more about this fascinating sky-reader!

In The Beginning

Depending on who you ask, Michel de Notredame, more commonly known as Nostradamus, was born on either December 14th or December 21st. One of nine siblings, he was born in the South of France in Saint-Rémy de Provence. As a child, Nostradamus rapidly progressed through school, learning Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and math. His grandfather, born Jewish but converted to avoid the Catholic Inquisition, introduced him to astrology, piquing the young savant’s interest in the study of celestial happenings and their impact on human life.

Nostradamus began his study of medicine at the ripe age of fourteen when he enrolled at the University of Avignon. Malheureusement, he had to leave the university after a year because of a Bubonic Plague (“La Peste”) outbreak. Nostradamus worked as an apothecary afterwards, traveling throughout the Franco-Italian countryside. His treatment of the plague moved away from the common practice of mercury potions, bloodletting, and garlic-soaked robes, opting for his signature “rose pill,” which was rich in Vitamin C. Despite how deliciously aromatic a rose pill sounds, historians and scientists nowadays attribute Nostradamus’ high cure rate to his novel treatment routines which included rigorous personal hygiene, removing infected corpus from city streets, and good ol’ fresh air.

The man of the hour: Nostradamus

He was finally able to complete his medical degree in 1525 at the University of Montpelier, where his penchant for astrology got him into hot water with Catholic priests from time to time. Now a certified university graduate, Michel de Nostradame officially changed his name to Nostradamus in an attempt to Latinize himself, which was all the rage in the most fashionable of medieval academic circles.

In 1531 Nastradamus was invited to Agen in France's southwest where he met his wife and had two children. Financially supported by Jules-Cesar Scaliger by scholar Jules-Cesar Scaliger, Nostradamus enjoyed monetary security and celebrity status because of his successful treatments. This posh life came to a swift end when Nostradamus’ wife and children died of the plague, and the great healer quickly fell out of public favor. Scaliger, ever the careerist, brutally dropped Nostradamus for fear of looking like he was sponsoring a fool. Unfortunately, Nostradamus didn’t have a talent agent or manager at the time to help him spin this tragic loss into a tell-all book deal.

What’s Your Sign?

A More Celestial-Minded Chapter

When Nostadamus was summoned to be tried by the Catholic Inquisition after making a joke in 1538, he said “No thanks,” and began bounding eastward out of Province through Italy, Greece, and Turkey. This journey was not only the original Eat, Pray, Love (don’t fact check me), but it was also the backbone of Nostradamus' psychic awakening. One account said that the man even met a group of Franciscan monks, one of which he predicted would become Pope. Low and behold, Felice Peretti, a monk he’d met, was ordained as Pope Sixtus V in 1585.

French Astrological Vocab For Your Next Reading

“C’est quoi, ton signe ?” - “What’s your sign?”

Planète maitresse - Ruling planet

“Mercure est en rétrograde.” - “Mercury is in retrograde.”

Thème astral - Birth chart

Retour de Saturne - Saturn return

Nostradamus returned to France in 1547 after spending what he believed to be adequate time avoiding the Inquisition. He once again took up treating plague victims, and settled in Salon-de-Provence where he married and had six children with Anne Ponsarde, a rich widow. He once again quickly ascended the ranks of medical notoriety for innovations in the treatment of plagues in Aix and Lyon. During this time, Nostradamus published two books, one a translation of Galen, the Roman Physician, and the other called the Traité des Fardemens, an apothecary cookbook that included both cosmetic and culinary recipes. Perhaps trying to drive up industry demand, many of the culinary recipes were based on the use of sugar, whose supply was regulated by the apothecaries’ guild of that time.

Despite publishing two books on medicine, Nostradamus’ fascination with the occult continued to grow. Allegedly, he spent many nights meditating in front of a bowl of water and herbs (which was NOT soup!) in order to transcend the mundane world and enter the spiritual realm. He had many visions, which helped him write his prophecies. Nostradamus wrote his first astrological almanac in 1550, incorporating his visions and astrological knowledge into digestible information for farmers and merchants. The success of this first almanac pushed Nostradamus to write more.

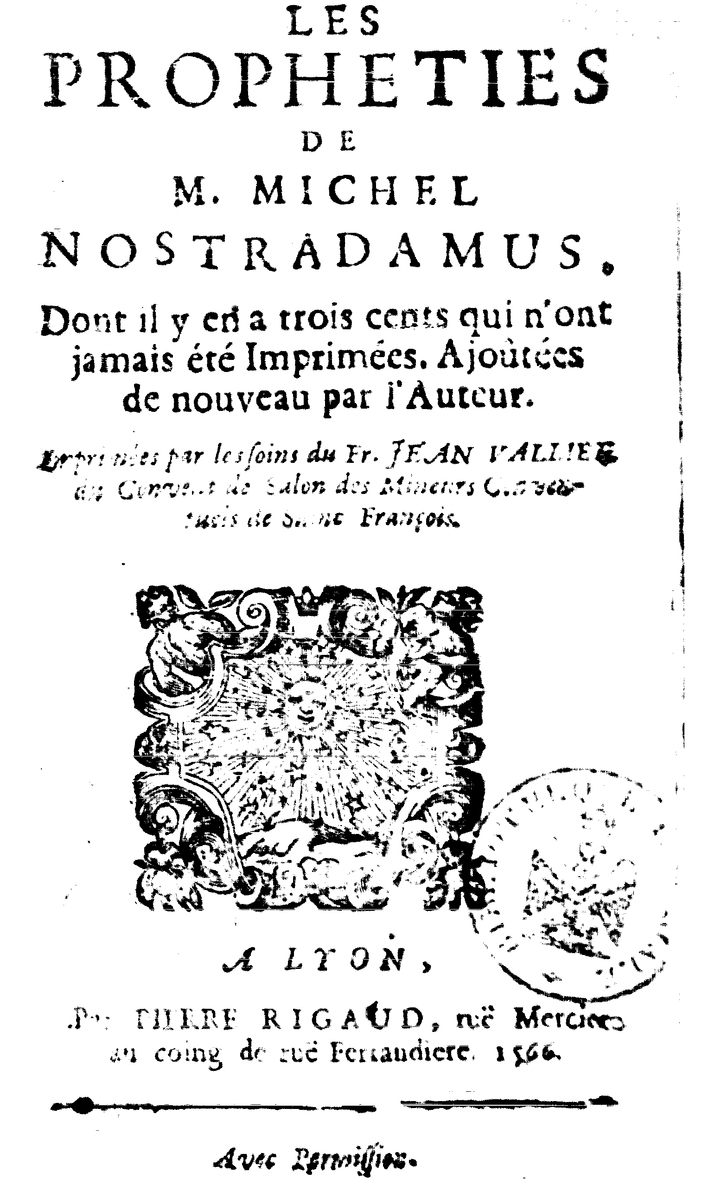

By 1554, Nostradamus had made his prophecies a key part of his almanacs. In an attempt to concentrate his creative energy into one work, Nostradamus began writing a ten-volume oeuvre called Centuries which would attempt to make one hundred predictions for the preceding two thousand years. In 1555, he published “Les Propheties,” a collection of his greatest hits that included major long term predictions. Nostradamus hid his mystic predictions behind quatrains (four-line versions that rhyme) and a linguistic potluck including French, Latin, Greek, Italian, and Provençal— a Southern French dialect. Nostradamus evaded persecution from the Catholic Church, and his writings were never condemned by the church’s book-regulating body, the Congregation of the Index. He did so by leaving his predictions detached from magical practice.

While some questioned Nostradamus’ sanity, or posited his ties to Satan, many more were enraptured by his prophecies. He entered the inner circles of Europe's elite, eventually catching the attention of Catherine de Medici, Queen Consort of Henri II. She summoned the seer to her court in Paris to draw up horoscopes for her children and was eventually made the court’s Physician-in-Ordinary to his court. In 1556, Nostradamus’ owned up to Catharine de Medici that one of his prophecies from Centuries I was most likely referring to King Henri II. Three years later, the prophecy came true. Here’s the text:

Le lyon jeune le vieux surmontera,

En champ bellique par singulier duelle,

Dans cage d’or les yeux luy creuera,

Deux classes une, puis mourir, mort cruelle

"The young lion will overcome the older one,

On the field of combat in a single battle;

He will pierce his eyes through a golden cage,

Two wounds made one, then he dies a cruel death."

In 1599, King Henri II jousted with younger nobleman Gabriel comte de Montgomery, seigneur de Lorges. In one last swing, Montgomery’s lance splintered in two, one piece slipping through the King’s visor, hitting his eye, and the other finding its way into his temple. King Henri then waited 10 days for the wound to finally deal its final blow on his life. Do you think the prophecy predicted the his death?

Nostradamus was critiqued by ordinary citizens and astrologers alike. Regarding his King Henri II prophecy, critics have said that a joust between friends shouldn’t necessarily be considered the “field of battle.” Additionally many professional astrologers of the era considered him incompetent and didn’t agree with his use of comparitive astrolgy to predict the future. Some believe that many of Nostradamus’ predictions were based on biblical depictions of the apocalypse as well as the writings of classical and medieval historians. He then matched with their respective astrological readings in the past before being rearranged and appropriated for the future.

Goodbye, Mr. ‘Damus

Nostradamus’ lifelong battles against gout and arthritis eventually took a turn for the worse when his gout developed into edema (dropsy) where large amounts of body fluid build up under the skin. Eventually, the untreated edema led to congestive heart failure, and Nostradamus died on July 1st, 1566.

Nostradamus’ writings are continually inspected by people today. Being so cryptic means that they are always up for interpretation, and some believe he correctly predicted events that occurred during the French Revolution. Nostradamus loved to predict apocalyptic phenomena, and most of his predictions dealt with war, murder, plagues, and other death-focused happenings. Some believe that he has predicted events ranging from the French Revolution to the development of the atomic bomb. Others believe that some prophecies are said to foretell future events that have not yet occurred. His writing’s vagueness has proven to be a fabulous vehicle to interpret and reinterpret what he has predicted. Think what you want about the validity of his predictions, but the man was a genius marketer whose written word left a legacy with viral staying power well beyond his body’s physical lifespan. Not sure what to think? Maybe it’s time to ask the stars.

Thanks for Reading!

Are you a fan of astrology? Comment down below, and be sure to share this article with a friend!

Thumbnail Photo by Josh Rangel

School Friends Are Cool Friends: My Time As A Language Assistant In France

What it’s like being an American in France during a pandemic.

by Brian Alcamo

With Back-to-School season upon us, I’ve found myself reflecting on what it was like to go back to a high school for the first time since graduating college. This high school wasn’t my alma mater, and it wasn’t even in my home country. The school didn’t have lockers, it didn’t have cheerleaders, and it didn’t have mystery meat hamburgers.

More specifically, I was looking for a redo. A year prior, I had spent a semester in Paris. The experience was less than stellar. Bouts of anxiety and difficulty in navigating an unexpected culture shock translated into me angstily denying myself a proper study abroad experience. I refrained from exploring the country in which I was privileged enough to have an extended stay, and I missed out on so many adventures because I was so caught up in the anguish of being far away from home for the first time. Despite my lackluster time in Paris, I left France with the creeping feeling of unfinished business. TAPIF, I had thought, was the second chance I needed. I would finally have the experience I’d dreamed of having, filled with travel, meaningful surface-level one-off exchanges with strangers (you know the kind), and ample opportunities to practice my French while opening up my worldview. I proudly sent out my application and awaited the results while finishing my final semester of college... until a certain virus knocked the world as we knew it right out of existence.

After a move home, a rushed goodbye to my friends, and a quick foray into the challenges of distance learning (all combined with your typical senioritis), I practically forgot about my application to go to France. “No way would they let us head over there during a global pandemic,” I repeatedly told myself and others. I wanted this to be true, since I wasn’t ready to leave the community I had just re-entered. COVID had turned out to be a strange opportunity to reconnect with my family and my hometown, and I was deep in the fog of familiarity. I spent April, May, and early June wondering if the program would be cancelled before receiving my acceptance letter. Then, against all odds, my opportunity to escape pandemic mundanity arrived in my email inbox with an unseasonably joyous “Felicitations !”

I had been accepted to teach at the secondary school level with the Academie de Lille,

My life from June to early September was also characterized by the anxiety of not knowing whether TAPIF would even pan out.

Despite the rising coronavirus tides and a late-start to the immigration process, TAPIF eventually issued the go-ahead for my visa along with a stipulation stating that I had ample leeway to make it to l'Hexagone. I was allowed to arrive as late as December 31st, 2020, if my visa processing took that long. My wishy-washy decision making process kept me and my loved ones on edge right up until the date I left. No one, including myself, thought I would follow through with it, but there I was, presenting my passport to the AirFrance employee working at check-in. When I got onto the plane, I realized just how lucky I was. The entire back section of Coach on a flight from New York’s JFK to Paris’s Charles de Gaule was completely empty, as if I had the entire airplane to myself. I was alone for the first time since rushedly moving home from college, but I felt a sense of freedom I hadn't felt since graduating high school.

Arriving in Lille–sweaty as can be with two suitcases and horrific breath after wearing an N95 mask for upwards of twelve hours on a plane and then a train–I was quickly elated by the feeling that I had made the right decision. I had taken a risk during a time when taking risks felt all the heavier. I had given myself an opportunity for post-college closure after a cancelled graduation ceremony that made life feel like a foggy false-start. I was able to launch myself when many launchpads were closed until further notice.

The fact that schools were physically open was the reason why I could go to France in the first place. It was also the only way I was able to stay sane during my time in Lille, with almost no other outlets to meet and engage with public life available to me during my stay. School was where I made friends. School was where I could talk, laugh, and be reminded that people existed outside of my computer screen. It kept me tethered to the real world when a combination of increased internet usage and culture shock threatened to completely detach me from reality.

My job as an English teaching assistant meant that I was to work in tandem with teachers’ lessons. I worked at both a lycée (high school) and a collège (middle school).

At the high school, the job typically consisted of me pulling out half a class at a time to give a presentation, have a discussion about American current events, play games, or supplement what a teacher was doing during the main lesson. Sometimes, I would do speaking exercises with the high schoolers to help them prepare for the Examen baccalauréat, which students take throughout their première and terminale years.

During my hours at the middle school, the teachers and I worked together in the same classroom, typically playing games designed to get the students to speak. While the high school was running on a hybrid model, the middle school’s classes were at full capacity and had more or less an unchanged rhythm to the school day. They still had recess–which was of top priority for both teachers and students alike.

In my freetime, I was often alone, but I was rarely lonely. I lived at the high school where I worked, which had dorms available for all of the assistants. The close quarters and confinement policies ensured that we had plenty of time for roommate bonding activities. After the lockdown announcement that came one week after my late arrival, one of my new friends made us lasagna as a way to build morale.

The restrictions in France were tough at times, but I appreciated the fact that there were even restrictions to begin with. I spent my free time writing, walking around, and going to whatever kinds of establishments were open at the time. The types of places that were allowed to be open changed every few weeks, and at times my most exciting excursion would be getting a haircut. Other times, we were able to go to non-essential stores, and I would spend a large portion of my days taking long, winding walks into the Vieux Lille to go window shopping. Since my teacher friends couldn’t just pop by the assistant dorms, we would try to get together for drinks and Sunday lunches when we could, sneaking around and loosely interpreting the rules du jour.

There were periods when life was more free. While I couldn’t spend the every-other-month two-week vacations galavanting through Europe like I dreamed of doing, I could still move around a little bit. I went to Lyon with two friends during the winter break and had the opportunity to go to Paris a handful of times as well. Life maintained some semblance of spontaneity and joie de vivre. Once, my American friend (who had been serendipitously put in the same city as I was) and I got beers to-go and sat down on an empty sidewalk overlooking the Tour Montparnasse.

The people of the north seemed to take COVID-19 rules more seriously. On my weekend trips to Paris, it was easier to find people sneaking out for a clandestine drink in the park. Further south in Lyon, people proudly and openly toted their after-work drinks to the park right after curfew. Up in Lille, the city shut down right at 6 p.m. (or 7, or 8:30, or 9, depending on what week it was).

Despite being in the north of France, which gets a bad rap for having horrible weather, the winter wasn’t as bad as people said it would be. Sometimes it snowed, but mostly the temperature remained above freezing.

Sometimes I wonder what my time would have been like if I had come to France during a "normal" year. I'd like to think it would have been filled with parties, bars, traveling, and other kinds of ephemeral activities that people love to spend money on. Instead, it was filled with long, aimless walks through the same picturesque streets day after day. Lille confiné was not the amusement park I'd been hoping for. Instead of being my playground, Lille was my labyrinth. Week after week, I'd fester and ponder and reflect during my long, ambling walks up Rue Armand Carrel, toward Saint Sauveur, and finally make my way towards Place d'Opera. The city served as a backdrop to the many milestones of growth I accomplished as each new COVID-19 safety measure made my already quiet life there even quieter.

So what's the upside of living in a foreign country during a pandemic? The same as its downside: the quiet. Although painful at times, silence and social retreat can do wonders for someone looking to unwind from a period of heightened extroversion. I did not grow up a Francophile, but every time I go to France, I love it more. The longer I stayed, the more I felt like I was becoming myself. Seeing new places, trying new foods, and doing fun activities is all good and fun, but I believe one of the bigger benefits of traveling is being far enough away from home to let all the noise and expectations and internalized judgements fall away until a person is left with only themselves. So that each step in an undiscovered city is also a step inward.

But eventually we must return home, as I had to do three weeks early when France finally decided to close its schools for a month to avoid the worst of a once-again surging case count. After the announcement to close schools was made, I quickly said goodbye to my friends. I cried in my bedroom with each goodbye, tearful at the thought of not seeing the people who had made my stay worthwhile as I spent the next week packing up. While I was glad I got to experience the feeling of being a detached traveler, I found myself preparing to miss my friends much more so than my solitary walks. I had sought the life of a vagabond, but I had been handed a community.

While my time in the country wasn’t what it could have been if I went during a different year, it was still educational in its own right, and I know I was extremely lucky. Not only because I got to go to France when almost no non-EU citizen was allowed into the country, but also because my post-college plans went largely unscathed by the brunt of the pandemic. And perhaps I’m even luckier, because now I have another perfect excuse to go back for another “redo.”

by Brian Alcamo

With Back-to-School season upon us, I’ve found myself reflecting on what it was like to go back to a high school for the first time since graduating college. This high school wasn’t my alma mater, and it wasn’t even in my home country. The school didn’t have lockers, it didn’t have cheerleaders, and it didn’t have mystery meat hamburgers. A little under a year ago, I made the courageous and foolish decision to move to France right before a new wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. I was given the opportunity through a program called TAPIF (Teaching Assistant Program In France) which I had applied to during my senior year of college back in December 2019, before COVID-19 was making national headlines. At the time, many of my friends were looking for or had already found their first post-college jobs, but I had my sights set on a different kind of experience: I wanted to live in France.

More specifically, I was looking for a redo. A year prior, I had spent a semester in Paris. The experience was less than stellar. Bouts of anxiety and difficulty in navigating an unexpected culture shock translated into me angstily denying myself a proper study abroad experience. I refrained from exploring the country in which I was privileged enough to have an extended stay, and I missed out on so many adventures because I was so caught up in the anguish of being far away from home for the first time. Despite my lackluster time in Paris, I left France with the creeping feeling of unfinished business. TAPIF, I had thought, was the second chance I needed. I would finally have the experience I’d dreamed of having, filled with travel, meaningful surface-level one-off exchanges with strangers (you know the kind), and ample opportunities to practice my French while opening up my worldview. I proudly sent out my application and awaited the results while finishing my final semester of college... until a certain virus knocked the world as we knew it right out of existence.

After a move home, a rushed goodbye to my friends, and a quick foray into the challenges of distance learning (all combined with your typical senioritis), I practically forgot about my application to go to France. “No way would they let us head over there during a global pandemic,” I repeatedly told myself and others. I wanted this to be true, since I wasn’t ready to leave the community I had just re-entered. COVID had turned out to be a strange opportunity to reconnect with my family and my hometown, and I was deep in the fog of familiarity. I spent April, May, and early June wondering if the program would be cancelled before receiving my acceptance letter. Then, against all odds, my opportunity to escape pandemic mundanity arrived in my email inbox with an unseasonably joyous “Felicitations !”

I had been accepted to teach at the secondary school level with the Academie de Lille, located in the extreme north of France, abutting Belgium and, by water, the United Kingdom. The schools I’d potentially be working at were in the best location possible, right outside of the city center. In the months leading up to my given start date, I toiled and tumulted over whether or not to leave the US. “Will it be worth it to go during a pandemic? I’ll miss my family and friends and not even be able to enjoy my time there. What if things lockdown?” My mind swam with what-ifs and worst-cases. Eventually, I began to receive emails from teachers I’d be working with. This communication, filled with humanity and kindness that hadn’t yet been part of the bureaucratic application process, was what kept my interest levels high enough to continue considering while all of the other data around me suggested I stay put.

My life from June to early September was also characterized by the anxiety of not knowing whether TAPIF would even pan out. I had dug my hands even further into my familial ties, relishing in outdoor reunions with childhood friends and my extended bloodline. By September, all of the rumors about a post-summer uptick in coronavirus cases were proving to be true, and I hadn’t yet received the green light to go ahead with the visa process. I felt like I was on call for an international move. I was stressed beyond compare, but a teeny tiny part of me loved to anguish over feeling like a diplomat waiting to be beckoned to a foreign land. At the same time, another teeny tiny part of me was desperate for the program to be cancelled out-right, so that I wouldn’t have to make my first big post-college decision for myself. I craved adventure, spontaneity, and detachment, but I was scared to be lonely, even more so because of pandemic restrictions. I watched the case numbers go up with a twisted sense of silent glee, hoping that the program would be cancelled and my fate would be taken out of my hands, and was nervous when France continued to insist that its schools were remaining open with in-person instruction.

Despite the rising coronavirus tides and a late-start to the immigration process, TAPIF eventually issued the go-ahead for my visa along with a stipulation stating that I had ample leeway to make it to l'Hexagone. I was allowed to arrive as late as December 31st, 2020, if my visa processing took that long. My wishy-washy decision making process kept me and my loved ones on edge right up until the date I left. No one, including myself, thought I would follow through with it, but there I was, presenting my passport to the AirFrance employee working at check-in. When I got onto the plane, I realized just how lucky I was. The entire back section of Coach on a flight from New York’s JFK to Paris’s Charles de Gaule was completely empty, as if I had the entire airplane to myself. I was alone for the first time since rushedly moving home from college, but I felt a sense of freedom I hadn't felt since graduating high school.

The empty airplane on my flight to France.

Arriving in Lille–sweaty as can be with two suitcases and horrific breath after wearing an N95 mask for upwards of twelve hours on a plane and then a train–I was quickly elated by the feeling that I had made the right decision. I had taken a risk during a time when taking risks felt all the heavier. I had given myself an opportunity for post-college closure after a cancelled graduation ceremony that made life feel like a foggy false-start. I was able to launch myself when many launchpads were closed until further notice.

The fact that schools were physically open was the reason why I could go to France in the first place. It was also the only way I was able to stay sane during my time in Lille, with almost no other outlets to meet and engage with public life available to me during my stay. School was where I made friends. School was where I could talk, laugh, and be reminded that people existed outside of my computer screen. It kept me tethered to the real world when a combination of increased internet usage and culture shock threatened to completely detach me from reality.

My job as an English teaching assistant meant that I was to work in tandem with teachers’ lessons. I worked at both a lycée (high school) and a collège (middle school). Regardless of grade level, the goal at both schools was simple: get the students to speak English.

At the high school, the job typically consisted of me pulling out half a class at a time to give a presentation, have a discussion about American current events, play games, or supplement what a teacher was doing during the main lesson. Sometimes, I would do speaking exercises with the high schoolers to help them prepare for the Examen baccalauréat, which students take throughout their premiere and terminale years.

During my hours at the middle school, the teachers and I worked together in the same classroom, typically playing games designed to get the students to speak. While the high school was running on a hybrid model, the middle school’s classes were at full capacity and had more or less an unchanged rhythm to the school day. They still had recess–which was of top priority for both teachers and students alike.

In my freetime, I was often alone, but I was rarely lonely. I lived at the high school where I worked, which had dorms available for all of the assistants. The close quarters and confinement policies ensured that we had plenty of time for roommate bonding activities. After the lockdown announcement that came one week after my late arrival, one of my new friends made us lasagna as a way to build morale. We would usually have drinks on Thursday nights, communing in our tiny windowless kitchen to discuss the week’s events and our cultural differences. Sometimes we would cook together, each of us preparing each other food or snacks from our country of origin. For Thanksgiving, I made them a pecan pie made out of almonds and walnuts because pecans were so hard to find in France.

Lille’s Botanical Gardens or Jardin des Plantes

The restrictions in France were tough at times, but I appreciated the fact that there were even restrictions to begin with. I spent my free time writing, walking around, and going to whatever kinds of establishments were open at the time. The types of places that were allowed to be open changed every few weeks, and at times my most exciting excursion would be getting a haircut. Other times, we were able to go to non-essential stores, and I would spend a large portion of my days taking long, winding walks into the Vieux Lille to go window shopping. Since my teacher friends couldn’t just pop by the assistant dorms, we would try to get together for drinks and Sunday lunches when we could, sneaking around and loosely interpreting the rules du jour.

There were periods when life was more free. While I couldn’t spend the every-other-month two-week vacations galavanting through Europe like I dreamed of doing, I could still move around a little bit. I went to Lyon with two friends during the winter break and had the opportunity to go to Paris a handful of times as well. Life maintained some semblance of spontaneity and joie de vivre. Once, my American friend (who had been serendipitously put in the same city as I was) and I got beers to-go and sat down on an empty sidewalk overlooking the Tour Montparnasse.

The people of the north seemed to take COVID-19 rules more seriously. On my weekend trips to Paris, it was easier to find people sneaking out for a clandestine drink in the park. Further south in Lyon, people proudly and openly toted their after-work drinks to the park right after curfew. Up in Lille, the city shut down right at 6 p.m. (or 7, or 8:30, or 9, depending on what week it was).

Despite being in the north of France, which gets a bad rap for having horrible weather, the winter wasn’t as bad as people said it would be. Sometimes it snowed, but mostly the temperature remained above freezing. I did have to take Vitamin D, because it was only sunny every few days (this wasn’t as depressing as it sounds).

Place de l’Opera in the snow

Sometimes I wonder what my time would have been like if I had come to France during a "normal" year. I'd like to think it would have been filled with parties, bars, traveling, and other kinds of ephemeral activities that people love to spend money on. Instead, it was filled with long, aimless walks through the same picturesque streets day after day. Lille confiné was not the amusement park I'd been hoping for. Instead of being my playground, Lille was my labyrinth. Week after week, I'd fester and ponder and reflect during my long, ambling walks up Rue Armand Carrel, toward Saint Sauveur, and finally make my way towards Place d'Opera. The city served as a backdrop to the many milestones of growth I accomplished as each new COVID-19 safety measure made my already quiet life there even quieter.

So what's the upside of living in a foreign country during a pandemic? The same as its downside: the quiet. Although painful at times, silence and social retreat can do wonders for someone looking to unwind from a period of heightened extroversion. I did not grow up a Francophile, but every time I go to France, I love it more. The longer I stayed, the more I felt like I was becoming myself. Seeing new places, trying new foods, and doing fun activities is all good and fun, but I believe one of the bigger benefits of traveling is being far enough away from home to let all the noise and expectations and internalized judgements fall away until a person is left with only themselves. So that each step in an undiscovered city is also a step inward.

But eventually we must return home, as I had to do three weeks early when France finally decided to close its schools for a month to avoid the worst of a once-again surging case count. After the announcement to close schools was made, I quickly said goodbye to my friends. I cried in my bedroom with each goodbye, tearful at the thought of not seeing the people who had made my stay worthwhile as I spent the next week packing up. While I was glad I got to experience the feeling of being a detached traveler, I found myself preparing to miss my friends much more so than my solitary walks. I had sought the life of a vagabond, but I had been handed a community.

While my time in the country wasn’t what it could have been if I went during a different year, it was still educational in its own right, and I know I was extremely lucky. Not only because I got to go to France when almost no non-EU citizen was allowed into the country, but also because my post-college plans went largely unscathed by the brunt of the pandemic. And perhaps I’m even luckier, because now I have another perfect excuse to go back for another “redo.”

Thanks for Reading!

What do you think of the idea of spending lockdown in a foreign country? Comment below, and be sure to share this post with a friend!

The Guillotine: A Revolutionary Blade

The story behind the infamous chopping block.

by Brian Alcamo

This week, France celebrates le Quatorze Juillet. In the United States, we know this day as Bastille Day. While the actual storming of the Bastille happened two years after the start of the French Revolution, it is one of the movement’s defining moments as it kicked off an era of violence and upheaval that inevitably overturned the French monarchy. The violence and havoc typical of the French Revolution was defined and symbolized by one special device: la guillotine.

Let’s Explore This Hauntingly Iconic Instrument Of Revolution!

If you think capitation by guillotine sounds gruesome, you should know that things used to be much worse. In pre-guillotine 1700s France, people were executed by having their four limbs stretched (and eventually ripped) apart by four oxen that would each run out from the executé’s body. Members of the upper-class could upgrade their execution to a less painful hanging or beheading. Luckily, people eventually caught on to the idea that this style of execution was perhaps a bit much, and in 1789, French physician Doctor Joseph Ignace Guillotin pushed for the invention of a new machine that would behead criminals “painlessly” (yeah, right). Not only did the doctor wish to make persecution less painful, he also wished to make it equal amongst the social classes. The doctor wished for the end of the death penalty entirely, and believed that a standard beheading device done in private could bridge the gap between the rather theatrical and brutal public dismembering and the eventual end of capital punishment.

Despite Doctor Guillotin’s supposedly revolutionary dream of an equal-opportunity beheader, other European countries had already beaten him to the punch (or, chop). In Scotland, a predecessor of the guillotine, known as the Maiden, was in use. but France’s guillotine was the first to be used at the institutional level. Doctor Guillotin worked with German engineer (and harpsichord maker) Thomas Schmidt to build the first guillotine, opting for a diagonal blade as opposed to a round one.

The invention of the guillotine came just in time for the French Revolution. After the storming of the Bastille on July 14th, 1789 (the Revolution’s peak), a new civilian code crafted by the National Assembly was put into place, that equalized the death penalty among France’s social classes. While this isn’t the ideal way for a campaign of equality to start out, it did make the earthly gateway to the Great Equalizer a bit more egalitarian. The first guillotining took place at Place de Greve in Paris on April 25th, 1792 when Nicolas Jacques Pelletier, a highway robber, got the inaugural chop. This kicked off the Reign of Terror, or la Terreur, which was a period of time in which thousands of people were sentenced to death. Despite only lasting about two years, this era is usually what people imagine when they think of the French Revolution. Many notable aristocrats died during this time, with King Louis XVI suffering a blow by the merciless blade on January 21, 1793.

Credit: Julia Suits

Some Revolutionary Vocab for Your French Flashcards:

Un citoyen - a citizen

La monarchie - The monarchy

Un.e paysan.nne - a peasant

Imposition - taxation

La peine capitale - Capital punishment/the death penalty

After the Revolution

After the Revolution, the guillotine remained as France’s capital punishment method of choice. Other European countries such as Greece, Sweden, and Switzerland also continued to use the guillotine, although the device never made much of a splash in the Western Hemisphere. Parisian guillotine sites moved around a bit before ending up in Grand Roquette prison in 1851. In 1870, a man named Leon Berger brought much-needed changes to the machine’s design, adding a spring system, a locking device, and a new release mechanism for the blade. These redesigns set the standard for all new guillotines moving forward.

This was the period of time where a study known as Prunier’s Experiment took place. Researchers had been trying to figure out if the head maintained some level of consciousness after decapitation. Scientists obtained the consent of Monsieur Theotime Prunier in 1879, a death-row sentence, and poked and prodded his head after he was struck by the guillotine. All they could note was that the face maintained an expression of astonishment after the death, but it did not respond to any stimuli.

By 1909, the guillotine was being used behind La Santé Prison. The final execution by guillotine was on September 10th, 1977 in Marseille when murderer Hamida Djandoubi was put to death. While he was the last execution in France, he was not the last to be condemned to execution, with those condemned afterwards being exhumed after the election of François Mitterand in 1981.

The guillotine’s roughly two centuries of notoriety may have come to a close, but its memory lives on as a symbol of what can happen when a thirst for wide-scale violence supersedes enlightened revolutionary thought.

Thanks for Reading!

How do you feel about the French Revolution? Tell us in the comments below, and make sure you share this post with a fellow French-fanatic!

Le Marais: "Gay Paris" and the Construction of an LGBTQIA+ mecca

Where are the hottest gay clubs in Paris these days? The Marais.

by Brian Alcamo

If you’ve ever been to Paris, you’ve most likely heard of and been to the Marais. Originally a swamp (the English translation of the word marais) and a home to poorer inhabitants, the neighborhood was quickly gentrified into one of Paris’s most sought after commercial zones. It is also Paris’s most well-known gay neighborhood.

For those not in the know, the Marais is located in Paris’s 3rd and 4th arrondissements, on the Right Bank, or Rive Droite, of the Seine. The main gay areas of the neighborhood are concentrated along and around Rue Sainte-Croix-de-la-Bretonnerie. Rue du Temple and the Rue Vieille-du-Temple are considered the quarter’s other main arteries. While the area today is easily identifiable with old architecture, expensive boutiques, and rainbow flags, the Marais wasn’t always the prime Parisian locale for LGBTQIA+ culture. It also wasn’t always a hot tourist destination.

Originally, from the mid 13th to 17th Century, le Marais was the place to be in Paris for French nobles. They built their urban mansions, or hotels particuliers (literally “private hotels”) around the modern-day Place des Vosges, then called the Place Royal. Eventually, the Marais’s popularity declined before turning to complete disarray during the French Revolution. For a long time, the Marais wasn’t filled with much in the way of fabulous queer nightlife. It was a place of poverty, and notably served as Paris’s Jewish neighborhood for decades (specifically in the part of the neighborhood known as the Pletzl).

The Place des Vosges

But just because the Marais wasn’t the place to be gay in Paris, doesn’t mean a gay neighborhood didn’t exist. During the twentieth century until the end of the 1970s, Paris’s queer center of gravity moved a few times. Paris first became a gay capital in the 1920s with its first “golden age” of gay life. Its status as a gay haven was (and is) rivaled only by Berlin on the European continent. Many notable queer artists and writers (such as Colette, Satie, and Gertrude Stein) championed the city as a gay paradise, particularly for gay women. This first gay neighborhoods were centered on La Butte Montmartre and Pigalle. During German Nazi rule in the 1930s, Berlin ceased to be queer friendly, and thus Paris was the number one destination for LGBT Europeans. After the war, Paris’s in-vogue gay neighborhood shifted for the first time to Saint-Germain-des-Prés (on the Left Bank of the Seine).

Towards the end of the 1950s, the neighborhood then migrated back to the Right Bank, this time near the Place de l’Opera and Rue Sainte-Anne. This location was considered by some to be Paris’s first gay neighborhood, since its existence was the first to be “known to Parisians.” Beforehand, the neighborhoods were more clandestine, even if they can be traced back to by historians and academics today.

After spending two decades near l’Opéra, Paris’s first gay bar, Le Village, opened on Rue du Platre in 1977 just south of the Marais. One theory as to why the neighborhood moved was because people were fed up with the increased commercialization and door-checks happening. Regardless of the reason, gay businesses and life began to flourish just a few blocks northeast in Marais proper afterwards.

It’s important to note that it was gay businesses (notably thanks to entrepreneur David Girard) that created the Marais-As-Queer-Capital, and not the migration of queer people’s living quarters. Not that many gay people live in the Marais. In fact, the Marais isn’t even necessarily thought of as a residential gay neighborhood, rather a gay center. Its shops and bars cater to a gay clientelle, but the residential real estate wasn’t and isn’t overwhelmingly populated by gay people. Unlike New York’s Hell’s Kitchen (previously Chelsea, and the West Village before that), the Marais was always a place LGBT people, notably gay men, spent their free time. They’ve used the area as a transient space, as their own playground before going back to their apartments all over the city.

Helpful Vocabulary When Talking About Gay Life in Paris

Un marais - A swamp

Un hôtel particulier - A French mansion or

literally “a private hotel”

L’âge d’or - The Golden age

Un bar - A bar

Aller boire un verre - To go get a drink

Prendre un verre - To have a drink

Aller en boîte - To go to the club

Faire la fête (teuf*) - To party

Research has shown that the number of same-sex households holding PACS (pacte civil de solidarité, or civil unions) is evenly distributed throughout the city, indicating that gay people live everywhere throughout Paris, not exclusively in the Marais. Perhaps this residential decentralization is why Paris’s gay community is considered to be less overt and less organized compared to New York’s or Berlin’s.

Despite the Parisian gay scene potentially being thought of as less “out there” compared to other queer capitals, its existence is still crucial to LGBTQIA+ identity and community in France and around the world. Regardless of where the “gayborhood du jour” is, these queer spaces help create a collective queer identity where people can be who they were born to be.

Thanks for Reading!

Thinking of visiting Paris anytime soon? Be sure to check out the Marais. Please leave this article a “like,” and share it with a friend (or two)!

Thumbnail photo by Sophie Louisnard.

What’s the Word? Exploring French Word Games and Puzzles

Build your vocabulary and score big!

by Brian Alcamo

French speakers love their language, so naturally they’d gravitate towards games that deal with it on an intimate level. Les jeux de lettres, or word games, are a great way to practice your French vocabulary and spelling while putting on your critical thinking cap. Just don’t confuse jeux de lettres (word games) with jeux de mots. The latter simply means wordplay, such as the puns of vocab geeks everywhere. Regardless of which game you try first, you’re sure to have a fun time practicing and playing at the same time. Not convinced? Keep reading to find your new favorite jeu de lettre.

A Quick Rundown

France is no stranger to word games and brain teasers. For starters, there are crossword puzzles. Invented in New York in the early 20th Century, crosswords, or mots croisés, made it to France in 1924. They made their debut as la mosaïque mystérieuse, and were made popular by novelist Tristan Bernard. He and others became notorious verbicrucistes (or cruciverbistes), a French word for a crossword puzzle enthusiast.

French-language crossword puzzles are typically smaller than their English-language counterparts. French crossword puzzles also eschew accent marks. For example, the words être and été may intersect. This means that there are more options for intersecting words, and even more of a challenge to your francophone brain. French crosswords attempt to limit the number of black squares, don’t have to be square or symmetrical, and they allow two-letter words. Notably, they number their grids using a chess-style grid system instead of number “Across” and “Down” lists.

If you want to mix things up, try checking out mots fléchés. Mots fléchés, or arrowwords, are arguably preferred to crossword puzzles in Europe. They are effectively still crossword puzzles, with a more accessible twist. Mots fléchés are typically considered to be easier than crossword puzzles, a sort of “gateway puzzle” if you will. Originating in Sweden, mots fléchés came to France by way of linguist Jacques Capelovici. Mots fléchés take the clues and put them directly into the puzzle, thus integrating the two in one neat grid. You can also try mots mêlés (also known as mots cachés), which are classic, tried and true word searches.

Word games and puzzles are a great way to increase your phonotactic awareness in your target language. Put simply, phonotactics are a language’s specific rules that govern where sounds, or phonemes, can be placed in a word or sentence. For example, English words cannot begin in [ŋ] (this is the International Phonetic Alphabet symbol for -ing). Playing word games and puzzles will help you pick out rules like this in French, which in turn will help you in deducing and constructing French words like a native speaker.

Watch Real Frenchies Play

Des chiffres et des lettres, is a French game show that’s a bit like wheel of fortune, except it also includes math. The show is an updated version of the old show Le mot le plus long, which is French for “the longest word.” The first round involves doing exciting things involving basic math. The second round is a bit like Wheel of Fortune-meets-Boggle.

Get Started!

Luckily, there’s no shortage of word games online. Le cruciverbiste has a ton of free mots croisés, mots fléchés, and mots mêlés. If you’re looking for a more modern game, look no further than your phone. The iOS App-Store has oodles of games to play. A notable stand-out is SpellTower Francais, a word game that plays kind of like Boggle-meets-Tetris. It’s a fun way to flex your word-crafting muscles while clearing rows upon rows of letters. All of these word games will force you to put your thinking cap on and while building your vocabulary. Pro-tip: keep a dictionary nearby to look up new words as you play, you’re bound to come across plenty!

Thanks for Reading!

What’s your favorite word game? Be sure to comment below, and share this post with friends.

(Thumbnail photo by Brett Jordan)

Lights, Camera, Action! A Primer on French Cinema

Pass le popcorn !

by Brian Alcamo

Agnès Varda, Bridget Bardot, François Truffaut, do any of these names ring a bell? If not, they should! France has a huge cinema culture. Not only is the country home to one of the largest film industries outside of the US, it was also the birthplace of many of the cinematic technologies we take for granted nowadays. A history of the artform runs deep in this hexagonal country, and it’s time to check it out.

A Super-Brèf History of French Cinema

So where does that history begin? It begins in Lyon, with les Frères Lumière. Auguste and Louis Lumiere, also known as the Lumière brothers, were kind of like France’s Wright brothers, in that they were brothers who invented something together. Growing up with a father in the photography industry, this dynamic duo took what they learned while growing up and developed the cinematograph. This three-in-one device was used to shoot, print, and project film.

In late 1895, the brothers released 10 very-short films at the Salon Indien du Grand Cafe in none other than Paris, France. The films dazzled their audience, who had never seen anything like it before. However, the film that embedded itself into the modern cinematic tradition the most was L’Arriveé d’un train en gare de La Ciotat, or “Arrival of a train at La Ciotat,” This film was not part of the original ten, but was instead showed for the first time in January 1896. The audience members were so new to the concept of cinema that they purportedly ran away from the screen, thinking that the train would come barrelling towards them!

A second early-cinema film that took the world by storm was Le voyage dans la lune (1902), which is widely considered the first science fiction film. Directed by magician-turned-filmmaker Georges Méliès, the film was the first to use many techniques and special effects that are the building blocks of modern editing methods.

After the dawn of the cinematic artform, French film went through several artistic movements: German (yes, German) Expressionism, La Nouvelle Vague, Left Bank Cinema, Le Cinéma Vérité, Le Cinéma du look, and others. It’s consistently evolved on its own, and in response to work being put out by Hollywood. Some say that the infamous Nouvelle Vague was created out of a reaction to the formulaic, studio-based films coming out of Los Angeles at the time.

French Cinema Today

French film is a strong industry, and receives substantial amounts of financial support from the government. Movie theaters are typically used as a refuge from sometimes unbearable summer heat, since so many french dwellings don’t have air conditioning. If you’re ever in France during a canicule, be sure to catch a movie to cool off while experiencing some culture.

To keep up with the latest in French entertainment news, you should keep your eyes on AlloCiné, a French website that combines elements of IMBD and Variety. You can search for information on your favorite shows and also get updates on the industry as a whole, all while your comprehension écrite.

If you want to get a romanticized glimpse into the French film industry, check out the series Dix Pour Cent. Named after the percent of money that agents typically get from an actor’s contract, the show follows the lives of four stressed-out Frenchies as they make deals with France’s biggest vedettes. The show is a great primer on the names of French movie stars, since every episode features a different big ticket actor playing a fictionalized version of themself. In the US, the show is known as Call My Agent! and is available on Netflix. If you need subtitles, try putting them in French instead of English to push your language learning to the next level.

Take a Dive into Some French Classics!

Thanks to streaming platforms, French-language movies and television are easily available online. They’re also a great way to practice your French, and to get a glimpse into the specificities of French culture. What’s your favorite French film? Be sure to comment below, and give this post a heart!

(Thumbnail photo by Michał Parzuchowski)

Celebrate Bastille Day 2020 While at Home

Join JP Linguistics and Time Out New York to celebrate Bastille Day 2020 along with amazing and authentic French Brands in New York City!

Bastille Day - A Symbol of Freedom and Liberty

Have you ever wondered what the big deal with Bastille Day and the French was? Well, you are in luck because on Tuesday, July 14th we will explain all virtually during a full-day celebration we have planned. Although this year marks the first time that Americans are banned from travelling to Europe because of the Covid-19 pandemic, we partnered with Time Out New York to bring you authentic French experiences in NYC that you can enjoy by tuning in to their Instagram account, @timeoutnewyork, starting at 9:00AM on July 14th. Our event is also including in United for Bastille Day, organized by the Consulate General of France. Keep scrolling for a brief history of Bastille Day and more details about the event.

Gravure de la Bastille, par Jean-François Rigaud, XVIIe s.© DEA PICTURE LIBRARY https://www.geo.fr/histoire/la-bastille-400-ans-d-histoire-161952

What is Bastille Day?

Bastille Day or Le 14 juillet is the national day of France. It is on July 14th 1789 that the Bastille was destroyed and marked the beginning of the Fall of the Monarchy and of the French Revolution. The Bastille was build in the 14th century to protect the city and it became a symbol of Tyranny that people wanted to take down, as it had become a prison for people who opposed the political system in place. Most of the people who were emprisonned in the Bastille did not even received a proper judgement, instead, they received a lettre de cachet from the King who would condemned them right away. The Bastille was therefor a symbole of Tyrannie and not one of Freedom. This is why French people do not refer to this day as Bastille Day but as Le 14 Juillet. On this day, French people celebrate the abolition of a Monarchie and the creation of a Republic with the current French Motto “ Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité”

How to Celebrate Bastille Day In 2020

Celebrating Bastille Day during a pandemic might seem like an impossible thing to do. But as we say in French, impossible n’est pas français (impossible is not French)! This year, JP Linguistics has partnered with Time Out New York to bring to you the best of French Culture in NYC, showcasing a true mark of Fraternité and Solidarité. Make sure to tune in on Tuesday, July 14th starting at 9:00AM via the Time Out New York Instagram account, @timeoutnewyork, to celebrate with us. You can see the full program below including LIVE streams from JP Linguistics, Albertine Bookstore, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, DJ Stoon, French Cheese Board, Maille, Bertrand Demontoux, BLVD Wine Bar, and Delice & Sarrasin.

Bastille Day 2020 Celebration Schedule:

9am: Learn how to make authentic French Toast during this kickoff event with JP Linguistics

10am: Take a tour of the adorable Albertine bookstore and settle in for a live children’s book reading

11am: Join Metropolitan Museum of Art art historian Kathy Galitz and Time Out national culture writer Howard Halle for a discussion of Monet's La Grenouillère

12pm: Say bonjour to some sick beats during a Bastille Day livestream set with DJ Stoon

1pm: Make the perfect cheese board with French Cheese Board

2pm: Maille’s official Mustard Sommelier (yes, that’s a real job) demonstrates how to cook two delicious, simple French recipes: A warmed raclette-and-chicken baguette sandwich and a berry hazelnut galette

3pm: We’re back with JP Linguistics for a look at the history of French fashion in both Paris and New York

4pm: Grab a glass for a virtual French Rosé wine tasting with Sommelier Bertrand Demontoux at BLVD Wine Bar in Long Island City

5pm: Learn how to prepare a vegan Cassoulet Toulousain with the inventive West Village restaurant, Delice & Sarrasin

Let us know if you can make it or have any questions in the comments below and we will answer them on the lives! A bientôt !

Autism Awareness in France

Rebecca McKee, owner of The 13th Child Autism & Behavioral Coaching, Inc., weighs in on the support for people with Autism in France. (Guest Blog!)

Currently, the whole wide world, as well as the world wide web, is experiencing a unique

moment. We are all dealing with COVID-19. Toutefois (however) the whole wide world and

the world wide web has been united with another probleme de santé (health problem) for decades. Autism, Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Asperger’s Syndrome, PDD (Pervasive Development Disorders), PDD-NOS (Pervasive Development Disorder Not Otherwise Specified): all of these names fall under the same parapluie (umbrella). The entire world has an autism problem.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (sometimes referred to in French as Trouble du Spectre de l’Autisme) has become one of those “things” now: “I know someone with autism,” “I have a friend who has someone in her family with autism,” “My neighbor’s daughter has autism,” ainsi de suite (and so on). Some countries are at the top of their game in their advocacy and support of les personnes autistes (people with autism). Unfortunately, France is not one of the leaders in this fight. But things are getting better.

The Council of Europe, basé a Strasbourg (based in Strausburg), focuses on droits

humains (human rights). Between the years 2004 to 2014 France was cited cinq fois (five times) for discriminating against people with autism spectrum disorder. According to the Council of Europe, France violated the rights of people avec (with) ASD to be educated in mainstream schools, as well as receiving vocational training. In 2016, The Committee on the Rights of the Child (a United Nations organization) expressed concerns that children with ASD continue to be subjected to violations of their rights within the borders of France.

There are many good ideas and great brains in France, and les gens veulent aider (people want to help). The French government is starting to take small steps to improve the situation for people with ASD. In 2005, France created ‘The Autism Plan’. This plan offered new dépistage (screening) and diagnosis recommendations for ASD. It also created ‘Autism Resource Centers’ in each of the nation’s administrative regions to screen children. These centers also offered advice to families about possible treatment options. Financial assistance information was also made available.

Une étape importante (an important step) was that the ‘Classification Française des Troubles Mentaux de l’Enfant et de l’Adolescent’ (French Classification for Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders) stopped defining autism spectrum disorder as a psychose (psychosis). This semantic change will ouvrir la porte (open the door) to hope, help, and a sense of community among families living and loving someone with autism spectrum disorder. This change also puts France on the same playing field of other countries with international diagnostic standards. Additional government plans have introduced specialized teaching units within some mainstream schools.

Further initiatives include: measures to increase access to specialized classrooms, better job training and housing options for adults with ASD. It is hopeful that France will rise to the occasion. We will surely see the effects of their efforts.

Guest blogger: Rebecca Mckee

Rebecca McKee is the owner of The 13th Child Autism & Behavioral Coaching, Inc. Rebecca has a Master’s Degree in Special Education, with a Concentration in Autism Spectrum Disorders. She is also a Board Certified Behavior Analysis (BCBA). Rebecca’s clients have ranged from babies to adults.

The philosophy of The 13th Child Autism & Behavioral Coaching, Inc. is for all people to enjoy a high quality of life including achievement, creativity, friendships, spirituality and wellness. Services can take place at the child’s home, school and community. Rebecca McKee lives in Brooklyn New York

Thumbnail photo by Ryoji Iwata

Large Scale French Graffiti

How do you put a painting on a Parisian rooftop? Start with les drones.

French graffiti artists Ella and Pitr have painted Europe's largest work of street art on a roof of a Paris convention centre. Covering 2.5 hectares, the image of an old woman intersected by the ring road around the French capital can be fully viewed only from the sky.

Only from high above can one see how it adds up to an image of an old woman, looking down at the traffic on the Périphérique, the busy ring road that surrounds the French capital. The duo stated that “Her eyes are half closed because she’s very bored by all the fast stuff around her…We wanted to find something with a lot of contrast with the geographic site,” which is full of traffic both by car and foot.

Photo: Objectif Aéro/Ludovic Delage

The duo gained access to the roof through an arrangement between city officials and Art en Ville, a group promoting urban art in public places. This isn’t the first time the duo has created projects like this. Ella + Pitr have created other large-scale works in France, Portugal, Chile, Canada and elsewhere since they met in the French city of Saint-Etienne in 2007.

The new work covers a surface equivalent to four football fields. It breaks the artists’ own record, set with a mural in Norway in 2015. Amazingly they completed the mural over eight days in June using acrylic paints diluted and loaded into spray cans.

The duo brilliantly used drones to create it while referring to aerial photos of the roof. Because of it’s location, even by standing on an adjacent rooftop, the full image is not visible and the Olivier Landes, the curator and founder of Art en Ville stated that “We’re counting on the Internet and the media to spread the aerial image, which will be viewed virtually, on a screen, like all works of urban art.”

The artwork itself will exist until 2022, when the hall is to be demolished as part of a renovation project to prepare the complex for the 2024 Olympic Games.

We hope you enjoyed learning about Large Scale French Graffiti! What are your thoughts on this new form of urban art? Does it add character to the city even though it can only be viewed online? Join the conversation below!

The French LGBTQ+ Reproductive Rights Debate

Women of all persuasions will soon share the same reproductive rights previously guaranteed only for those in heterosexual couples.

France's Prime Minister Edouard Philippe announced to the National Assembly on Wednesday that by the end of September that Parliament will be reviewing a bill that will include an extension of medically assisted reproduction for all women, including those who are single and lesbian couples which was one of President Emmanuel Macron’s main campaign promises. The prime minister said that the bill was ready, but the content of it was still to be made public.

Minister of Justice Nicole Belloubet spoke to French radio France Inter about the 3 options being considered: "Either we extend the current legal regime to homosexual couples and single women or we create a special status for all children born from IVF with a third donor or we create a special status only for female couples and single women."

Another major point of debate will be the children's access to their origins, thus allowing all French citizens access to records about how, when, and where they were conceived. The details of this discussion are still under wraps, but should the bill pass, it will be a milestone for the fight for reproductive rights transparency.

We hope you’ve enjoyed learning about The French LGBTQ+ Reproductive Rights Debate! What are your thoughts on this new bill? Join the conversation below!

Budget Friendly Luxury French Flights

Coach is cramped. Treat yourself and upgrade your flight without breaking the bank.

Looking to take a luxury trip to France this summer without breaking the budget? If you’re willing to depart from New York City, you’re in luck! La Compagnie has announced round-trip flights from New York to Paris for just $1,000 on their business-class only fleet.

The airline launched in 2014 as a business-only option for those making the trip across the Atlantic and haven’t stopped innovating since. In September 2017, the airline announced that it was offering all-you-can-fly passes for its Newark to Paris route, costing $40,000 per year. In 2018, La Compagnie relocated its Paris operations from Charles de Gaulle Airport to Orly Airport and announced a new seasonal service to Nice Côte d'Azur Airport from Newark. Most recently, in May 2019, the airline took delivery of its first Airbus A321neo which has caused quite a conversation in the airline industry.

Why the excitement about this jet? For starters, every seat on board becomes a fully lie-flat bed and free and unlimited Wi-Fi for all passengers. The deal also includes lounge access at the airports on either side, two checked bags, wine and champagne on board, noise canceling in-flight headsets, and, best of all, a Maison Kayser croissant in your sea upon arrival.

Not ready to pull the trigger just yet? Be sure to check in on their official site for more promotions!

We hope you’ve enjoyed learning about Budget Friendly Luxury French Flights! Want to make sure you’re prepared to experience the culture of France when you arrive? Our native instructors and culturally immersive group classes will have you conversing in French in no time! Click below to learn more.

Debating The Reconstruction of Notre Dame

Can the famed cathedral be rebuilt by the 2024 Paris Olympics?