School Friends Are Cool Friends: My Time As A Language Assistant In France

What it’s like being an American in France during a pandemic.

by Brian Alcamo

With Back-to-School season upon us, I’ve found myself reflecting on what it was like to go back to a high school for the first time since graduating college. This high school wasn’t my alma mater, and it wasn’t even in my home country. The school didn’t have lockers, it didn’t have cheerleaders, and it didn’t have mystery meat hamburgers.

More specifically, I was looking for a redo. A year prior, I had spent a semester in Paris. The experience was less than stellar. Bouts of anxiety and difficulty in navigating an unexpected culture shock translated into me angstily denying myself a proper study abroad experience. I refrained from exploring the country in which I was privileged enough to have an extended stay, and I missed out on so many adventures because I was so caught up in the anguish of being far away from home for the first time. Despite my lackluster time in Paris, I left France with the creeping feeling of unfinished business. TAPIF, I had thought, was the second chance I needed. I would finally have the experience I’d dreamed of having, filled with travel, meaningful surface-level one-off exchanges with strangers (you know the kind), and ample opportunities to practice my French while opening up my worldview. I proudly sent out my application and awaited the results while finishing my final semester of college... until a certain virus knocked the world as we knew it right out of existence.

After a move home, a rushed goodbye to my friends, and a quick foray into the challenges of distance learning (all combined with your typical senioritis), I practically forgot about my application to go to France. “No way would they let us head over there during a global pandemic,” I repeatedly told myself and others. I wanted this to be true, since I wasn’t ready to leave the community I had just re-entered. COVID had turned out to be a strange opportunity to reconnect with my family and my hometown, and I was deep in the fog of familiarity. I spent April, May, and early June wondering if the program would be cancelled before receiving my acceptance letter. Then, against all odds, my opportunity to escape pandemic mundanity arrived in my email inbox with an unseasonably joyous “Felicitations !”

I had been accepted to teach at the secondary school level with the Academie de Lille,

My life from June to early September was also characterized by the anxiety of not knowing whether TAPIF would even pan out.

Despite the rising coronavirus tides and a late-start to the immigration process, TAPIF eventually issued the go-ahead for my visa along with a stipulation stating that I had ample leeway to make it to l'Hexagone. I was allowed to arrive as late as December 31st, 2020, if my visa processing took that long. My wishy-washy decision making process kept me and my loved ones on edge right up until the date I left. No one, including myself, thought I would follow through with it, but there I was, presenting my passport to the AirFrance employee working at check-in. When I got onto the plane, I realized just how lucky I was. The entire back section of Coach on a flight from New York’s JFK to Paris’s Charles de Gaule was completely empty, as if I had the entire airplane to myself. I was alone for the first time since rushedly moving home from college, but I felt a sense of freedom I hadn't felt since graduating high school.

Arriving in Lille–sweaty as can be with two suitcases and horrific breath after wearing an N95 mask for upwards of twelve hours on a plane and then a train–I was quickly elated by the feeling that I had made the right decision. I had taken a risk during a time when taking risks felt all the heavier. I had given myself an opportunity for post-college closure after a cancelled graduation ceremony that made life feel like a foggy false-start. I was able to launch myself when many launchpads were closed until further notice.

The fact that schools were physically open was the reason why I could go to France in the first place. It was also the only way I was able to stay sane during my time in Lille, with almost no other outlets to meet and engage with public life available to me during my stay. School was where I made friends. School was where I could talk, laugh, and be reminded that people existed outside of my computer screen. It kept me tethered to the real world when a combination of increased internet usage and culture shock threatened to completely detach me from reality.

My job as an English teaching assistant meant that I was to work in tandem with teachers’ lessons. I worked at both a lycée (high school) and a collège (middle school).

At the high school, the job typically consisted of me pulling out half a class at a time to give a presentation, have a discussion about American current events, play games, or supplement what a teacher was doing during the main lesson. Sometimes, I would do speaking exercises with the high schoolers to help them prepare for the Examen baccalauréat, which students take throughout their première and terminale years.

During my hours at the middle school, the teachers and I worked together in the same classroom, typically playing games designed to get the students to speak. While the high school was running on a hybrid model, the middle school’s classes were at full capacity and had more or less an unchanged rhythm to the school day. They still had recess–which was of top priority for both teachers and students alike.

In my freetime, I was often alone, but I was rarely lonely. I lived at the high school where I worked, which had dorms available for all of the assistants. The close quarters and confinement policies ensured that we had plenty of time for roommate bonding activities. After the lockdown announcement that came one week after my late arrival, one of my new friends made us lasagna as a way to build morale.

The restrictions in France were tough at times, but I appreciated the fact that there were even restrictions to begin with. I spent my free time writing, walking around, and going to whatever kinds of establishments were open at the time. The types of places that were allowed to be open changed every few weeks, and at times my most exciting excursion would be getting a haircut. Other times, we were able to go to non-essential stores, and I would spend a large portion of my days taking long, winding walks into the Vieux Lille to go window shopping. Since my teacher friends couldn’t just pop by the assistant dorms, we would try to get together for drinks and Sunday lunches when we could, sneaking around and loosely interpreting the rules du jour.

There were periods when life was more free. While I couldn’t spend the every-other-month two-week vacations galavanting through Europe like I dreamed of doing, I could still move around a little bit. I went to Lyon with two friends during the winter break and had the opportunity to go to Paris a handful of times as well. Life maintained some semblance of spontaneity and joie de vivre. Once, my American friend (who had been serendipitously put in the same city as I was) and I got beers to-go and sat down on an empty sidewalk overlooking the Tour Montparnasse.

The people of the north seemed to take COVID-19 rules more seriously. On my weekend trips to Paris, it was easier to find people sneaking out for a clandestine drink in the park. Further south in Lyon, people proudly and openly toted their after-work drinks to the park right after curfew. Up in Lille, the city shut down right at 6 p.m. (or 7, or 8:30, or 9, depending on what week it was).

Despite being in the north of France, which gets a bad rap for having horrible weather, the winter wasn’t as bad as people said it would be. Sometimes it snowed, but mostly the temperature remained above freezing.

Sometimes I wonder what my time would have been like if I had come to France during a "normal" year. I'd like to think it would have been filled with parties, bars, traveling, and other kinds of ephemeral activities that people love to spend money on. Instead, it was filled with long, aimless walks through the same picturesque streets day after day. Lille confiné was not the amusement park I'd been hoping for. Instead of being my playground, Lille was my labyrinth. Week after week, I'd fester and ponder and reflect during my long, ambling walks up Rue Armand Carrel, toward Saint Sauveur, and finally make my way towards Place d'Opera. The city served as a backdrop to the many milestones of growth I accomplished as each new COVID-19 safety measure made my already quiet life there even quieter.

So what's the upside of living in a foreign country during a pandemic? The same as its downside: the quiet. Although painful at times, silence and social retreat can do wonders for someone looking to unwind from a period of heightened extroversion. I did not grow up a Francophile, but every time I go to France, I love it more. The longer I stayed, the more I felt like I was becoming myself. Seeing new places, trying new foods, and doing fun activities is all good and fun, but I believe one of the bigger benefits of traveling is being far enough away from home to let all the noise and expectations and internalized judgements fall away until a person is left with only themselves. So that each step in an undiscovered city is also a step inward.

But eventually we must return home, as I had to do three weeks early when France finally decided to close its schools for a month to avoid the worst of a once-again surging case count. After the announcement to close schools was made, I quickly said goodbye to my friends. I cried in my bedroom with each goodbye, tearful at the thought of not seeing the people who had made my stay worthwhile as I spent the next week packing up. While I was glad I got to experience the feeling of being a detached traveler, I found myself preparing to miss my friends much more so than my solitary walks. I had sought the life of a vagabond, but I had been handed a community.

While my time in the country wasn’t what it could have been if I went during a different year, it was still educational in its own right, and I know I was extremely lucky. Not only because I got to go to France when almost no non-EU citizen was allowed into the country, but also because my post-college plans went largely unscathed by the brunt of the pandemic. And perhaps I’m even luckier, because now I have another perfect excuse to go back for another “redo.”

by Brian Alcamo

With Back-to-School season upon us, I’ve found myself reflecting on what it was like to go back to a high school for the first time since graduating college. This high school wasn’t my alma mater, and it wasn’t even in my home country. The school didn’t have lockers, it didn’t have cheerleaders, and it didn’t have mystery meat hamburgers. A little under a year ago, I made the courageous and foolish decision to move to France right before a new wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. I was given the opportunity through a program called TAPIF (Teaching Assistant Program In France) which I had applied to during my senior year of college back in December 2019, before COVID-19 was making national headlines. At the time, many of my friends were looking for or had already found their first post-college jobs, but I had my sights set on a different kind of experience: I wanted to live in France.

More specifically, I was looking for a redo. A year prior, I had spent a semester in Paris. The experience was less than stellar. Bouts of anxiety and difficulty in navigating an unexpected culture shock translated into me angstily denying myself a proper study abroad experience. I refrained from exploring the country in which I was privileged enough to have an extended stay, and I missed out on so many adventures because I was so caught up in the anguish of being far away from home for the first time. Despite my lackluster time in Paris, I left France with the creeping feeling of unfinished business. TAPIF, I had thought, was the second chance I needed. I would finally have the experience I’d dreamed of having, filled with travel, meaningful surface-level one-off exchanges with strangers (you know the kind), and ample opportunities to practice my French while opening up my worldview. I proudly sent out my application and awaited the results while finishing my final semester of college... until a certain virus knocked the world as we knew it right out of existence.

After a move home, a rushed goodbye to my friends, and a quick foray into the challenges of distance learning (all combined with your typical senioritis), I practically forgot about my application to go to France. “No way would they let us head over there during a global pandemic,” I repeatedly told myself and others. I wanted this to be true, since I wasn’t ready to leave the community I had just re-entered. COVID had turned out to be a strange opportunity to reconnect with my family and my hometown, and I was deep in the fog of familiarity. I spent April, May, and early June wondering if the program would be cancelled before receiving my acceptance letter. Then, against all odds, my opportunity to escape pandemic mundanity arrived in my email inbox with an unseasonably joyous “Felicitations !”

I had been accepted to teach at the secondary school level with the Academie de Lille, located in the extreme north of France, abutting Belgium and, by water, the United Kingdom. The schools I’d potentially be working at were in the best location possible, right outside of the city center. In the months leading up to my given start date, I toiled and tumulted over whether or not to leave the US. “Will it be worth it to go during a pandemic? I’ll miss my family and friends and not even be able to enjoy my time there. What if things lockdown?” My mind swam with what-ifs and worst-cases. Eventually, I began to receive emails from teachers I’d be working with. This communication, filled with humanity and kindness that hadn’t yet been part of the bureaucratic application process, was what kept my interest levels high enough to continue considering while all of the other data around me suggested I stay put.

My life from June to early September was also characterized by the anxiety of not knowing whether TAPIF would even pan out. I had dug my hands even further into my familial ties, relishing in outdoor reunions with childhood friends and my extended bloodline. By September, all of the rumors about a post-summer uptick in coronavirus cases were proving to be true, and I hadn’t yet received the green light to go ahead with the visa process. I felt like I was on call for an international move. I was stressed beyond compare, but a teeny tiny part of me loved to anguish over feeling like a diplomat waiting to be beckoned to a foreign land. At the same time, another teeny tiny part of me was desperate for the program to be cancelled out-right, so that I wouldn’t have to make my first big post-college decision for myself. I craved adventure, spontaneity, and detachment, but I was scared to be lonely, even more so because of pandemic restrictions. I watched the case numbers go up with a twisted sense of silent glee, hoping that the program would be cancelled and my fate would be taken out of my hands, and was nervous when France continued to insist that its schools were remaining open with in-person instruction.

Despite the rising coronavirus tides and a late-start to the immigration process, TAPIF eventually issued the go-ahead for my visa along with a stipulation stating that I had ample leeway to make it to l'Hexagone. I was allowed to arrive as late as December 31st, 2020, if my visa processing took that long. My wishy-washy decision making process kept me and my loved ones on edge right up until the date I left. No one, including myself, thought I would follow through with it, but there I was, presenting my passport to the AirFrance employee working at check-in. When I got onto the plane, I realized just how lucky I was. The entire back section of Coach on a flight from New York’s JFK to Paris’s Charles de Gaule was completely empty, as if I had the entire airplane to myself. I was alone for the first time since rushedly moving home from college, but I felt a sense of freedom I hadn't felt since graduating high school.

The empty airplane on my flight to France.

Arriving in Lille–sweaty as can be with two suitcases and horrific breath after wearing an N95 mask for upwards of twelve hours on a plane and then a train–I was quickly elated by the feeling that I had made the right decision. I had taken a risk during a time when taking risks felt all the heavier. I had given myself an opportunity for post-college closure after a cancelled graduation ceremony that made life feel like a foggy false-start. I was able to launch myself when many launchpads were closed until further notice.

The fact that schools were physically open was the reason why I could go to France in the first place. It was also the only way I was able to stay sane during my time in Lille, with almost no other outlets to meet and engage with public life available to me during my stay. School was where I made friends. School was where I could talk, laugh, and be reminded that people existed outside of my computer screen. It kept me tethered to the real world when a combination of increased internet usage and culture shock threatened to completely detach me from reality.

My job as an English teaching assistant meant that I was to work in tandem with teachers’ lessons. I worked at both a lycée (high school) and a collège (middle school). Regardless of grade level, the goal at both schools was simple: get the students to speak English.

At the high school, the job typically consisted of me pulling out half a class at a time to give a presentation, have a discussion about American current events, play games, or supplement what a teacher was doing during the main lesson. Sometimes, I would do speaking exercises with the high schoolers to help them prepare for the Examen baccalauréat, which students take throughout their premiere and terminale years.

During my hours at the middle school, the teachers and I worked together in the same classroom, typically playing games designed to get the students to speak. While the high school was running on a hybrid model, the middle school’s classes were at full capacity and had more or less an unchanged rhythm to the school day. They still had recess–which was of top priority for both teachers and students alike.

In my freetime, I was often alone, but I was rarely lonely. I lived at the high school where I worked, which had dorms available for all of the assistants. The close quarters and confinement policies ensured that we had plenty of time for roommate bonding activities. After the lockdown announcement that came one week after my late arrival, one of my new friends made us lasagna as a way to build morale. We would usually have drinks on Thursday nights, communing in our tiny windowless kitchen to discuss the week’s events and our cultural differences. Sometimes we would cook together, each of us preparing each other food or snacks from our country of origin. For Thanksgiving, I made them a pecan pie made out of almonds and walnuts because pecans were so hard to find in France.

Lille’s Botanical Gardens or Jardin des Plantes

The restrictions in France were tough at times, but I appreciated the fact that there were even restrictions to begin with. I spent my free time writing, walking around, and going to whatever kinds of establishments were open at the time. The types of places that were allowed to be open changed every few weeks, and at times my most exciting excursion would be getting a haircut. Other times, we were able to go to non-essential stores, and I would spend a large portion of my days taking long, winding walks into the Vieux Lille to go window shopping. Since my teacher friends couldn’t just pop by the assistant dorms, we would try to get together for drinks and Sunday lunches when we could, sneaking around and loosely interpreting the rules du jour.

There were periods when life was more free. While I couldn’t spend the every-other-month two-week vacations galavanting through Europe like I dreamed of doing, I could still move around a little bit. I went to Lyon with two friends during the winter break and had the opportunity to go to Paris a handful of times as well. Life maintained some semblance of spontaneity and joie de vivre. Once, my American friend (who had been serendipitously put in the same city as I was) and I got beers to-go and sat down on an empty sidewalk overlooking the Tour Montparnasse.

The people of the north seemed to take COVID-19 rules more seriously. On my weekend trips to Paris, it was easier to find people sneaking out for a clandestine drink in the park. Further south in Lyon, people proudly and openly toted their after-work drinks to the park right after curfew. Up in Lille, the city shut down right at 6 p.m. (or 7, or 8:30, or 9, depending on what week it was).

Despite being in the north of France, which gets a bad rap for having horrible weather, the winter wasn’t as bad as people said it would be. Sometimes it snowed, but mostly the temperature remained above freezing. I did have to take Vitamin D, because it was only sunny every few days (this wasn’t as depressing as it sounds).

Place de l’Opera in the snow

Sometimes I wonder what my time would have been like if I had come to France during a "normal" year. I'd like to think it would have been filled with parties, bars, traveling, and other kinds of ephemeral activities that people love to spend money on. Instead, it was filled with long, aimless walks through the same picturesque streets day after day. Lille confiné was not the amusement park I'd been hoping for. Instead of being my playground, Lille was my labyrinth. Week after week, I'd fester and ponder and reflect during my long, ambling walks up Rue Armand Carrel, toward Saint Sauveur, and finally make my way towards Place d'Opera. The city served as a backdrop to the many milestones of growth I accomplished as each new COVID-19 safety measure made my already quiet life there even quieter.

So what's the upside of living in a foreign country during a pandemic? The same as its downside: the quiet. Although painful at times, silence and social retreat can do wonders for someone looking to unwind from a period of heightened extroversion. I did not grow up a Francophile, but every time I go to France, I love it more. The longer I stayed, the more I felt like I was becoming myself. Seeing new places, trying new foods, and doing fun activities is all good and fun, but I believe one of the bigger benefits of traveling is being far enough away from home to let all the noise and expectations and internalized judgements fall away until a person is left with only themselves. So that each step in an undiscovered city is also a step inward.

But eventually we must return home, as I had to do three weeks early when France finally decided to close its schools for a month to avoid the worst of a once-again surging case count. After the announcement to close schools was made, I quickly said goodbye to my friends. I cried in my bedroom with each goodbye, tearful at the thought of not seeing the people who had made my stay worthwhile as I spent the next week packing up. While I was glad I got to experience the feeling of being a detached traveler, I found myself preparing to miss my friends much more so than my solitary walks. I had sought the life of a vagabond, but I had been handed a community.

While my time in the country wasn’t what it could have been if I went during a different year, it was still educational in its own right, and I know I was extremely lucky. Not only because I got to go to France when almost no non-EU citizen was allowed into the country, but also because my post-college plans went largely unscathed by the brunt of the pandemic. And perhaps I’m even luckier, because now I have another perfect excuse to go back for another “redo.”

Thanks for Reading!

What do you think of the idea of spending lockdown in a foreign country? Comment below, and be sure to share this post with a friend!

L'Académie Française: Making Sure Learning French Is Never Too Easy

The birthplace of your favorite rules and regulations!

by Brian Alcamo

France is governed by the French government, but French is governed by L’Academie Française (in French, it is spelled L’Academie francaise, the French don’t seem to be big fans of titles with too many capital letters). This centuries-old body is the reason why French learners (and native speakers, too) spend countless hours trying to remember painstaking rules such as having to make a past participle agree in gender and number with a direct object if said direct object is placed before the verb. For example:

Est-ce que tu as acheté le livre ? Oui, je l’ai acheté.

Est-ce que tu as acheté les fleurs ? Oui, je les ai achetées.

This particular rule is something that not even some computer spell check systems can get right. To be fair, this is pretty cool. You can make a computer learn to do plenty of things, but it will never score a 20/20 on its comprehension écrite. That being said, it goes to show just how many French writing rules are no longer supported by the modern day spoken language. The two verbs, ai acheté and ai achetees, are pronounced the exact same way.

But what’s this Académie’s whole deal anyway, and why does it seem to have a proverbial stick up its proverbial you-know-what?

How the Académie Française Came to Be

The year is 1635. The king is Louis XIII. Cardinal (de) Richelieu continues to exercise his control over the young king, and gets himself named “le chef et le protecteur,” or “Chief and Protector” of the newly created Acadmie Française. This novel language-governing body may be today’s most notorious, but it was not the first. Richelieu was inspired by Florence’s Accademia della Crusca, an Italian organization

The flowery language of the organization’s mission statement declares that the Academie’s function is to create certain rules for the French language that will render it “pure,” “eloquent,” and “capable of engaging with the arts and sciences.” The mission statement also likens a nation’s arts and sciences to its arms. This link between language and military prowess is a reminder that at the end of the day, l’Academie is still a government body looking to exercise power.

Given that the Académie Française was constructed during the monarchical phase of France’s history, you might be wondering about what happened to it during the Revolution. From 1795 to 1816, the Academie Française ceased to exist. Along with other royal academies, it was abolished by the National Convention before being reinstated by some guy named Napoleon Bonaparte. Since the dawn of the French Republic, the original role of “Le chef et le protecteur” is fulfilled by the sitting French President.

Who’s Who and What’s What

The Académie is made up of forty nerds members, know as Les Immortels. Some of these members have been literary powerhouses: Voltaire, Victor Hugo, Eugene Ionesco among them. To become a member, you have to apply to fill a vacant position, rather than applying to be a member in general. If someone is fit for the role, they are voted in by the current immortels. At meetings, members have to wear l’habit vert, a special green outfit. Funnily enough, the color green was chosen out of process of elimination, according to Henri Lavedan.

Over time, the organization has changed its mission to be a more holistic one, with the goal of creating a language and writing system that is to be used by everyone, not just arts and sciences hotshots. France’s national love for its languages means that L’Académie Française remains a culturally relevant part of the government. Whole swaths of people react viscerally whenever the Académie changes something, and it's not only French teachers who are startled.

Back in 2016, the Académie made it acceptable to leave the accent circonflexe (the carrot) off of certain words. They also recently changed the spelling of the word “onion” (from oignon to ognon) for some quirky reason. After some people expressed concerns about the changes, the academie has ensured that both old and new spellings will be considered “correct.”

More controversially, the Académie has also contested the feminization of French nouns. It insists that regardless of a person’s gender, they must always use the masculine form of a noun if there is no feminine form readily available. Le ministre will always be le ministre, never la ministre, regardless of the gender of the ministre.

Now, don’t get us wrong. Languages do need some sort of decided-upon rules for governing spelling and grammar (mostly spelling). But problems arise when these rules are decided by an elite group of educated people. It can create issues of class equality, with spelling rules easily becoming arcane because of natural changes in pronunciation. When spelling and grammar no longer reflect spoken language, and instead represent literary achievement, who do these rules really serve?

Thanks for Reading!

Thanks for reading this blog post. Next time you get upset about a mispelled word that still “looks right,” or are thrilled by a beautifully written French novel, you can thank the Académie Française. Be sure to give this post a “heart,” and to share it with a friend!

What’s the Word? Exploring French Word Games and Puzzles

Build your vocabulary and score big!

by Brian Alcamo

French speakers love their language, so naturally they’d gravitate towards games that deal with it on an intimate level. Les jeux de lettres, or word games, are a great way to practice your French vocabulary and spelling while putting on your critical thinking cap. Just don’t confuse jeux de lettres (word games) with jeux de mots. The latter simply means wordplay, such as the puns of vocab geeks everywhere. Regardless of which game you try first, you’re sure to have a fun time practicing and playing at the same time. Not convinced? Keep reading to find your new favorite jeu de lettre.

A Quick Rundown

France is no stranger to word games and brain teasers. For starters, there are crossword puzzles. Invented in New York in the early 20th Century, crosswords, or mots croisés, made it to France in 1924. They made their debut as la mosaïque mystérieuse, and were made popular by novelist Tristan Bernard. He and others became notorious verbicrucistes (or cruciverbistes), a French word for a crossword puzzle enthusiast.

French-language crossword puzzles are typically smaller than their English-language counterparts. French crossword puzzles also eschew accent marks. For example, the words être and été may intersect. This means that there are more options for intersecting words, and even more of a challenge to your francophone brain. French crosswords attempt to limit the number of black squares, don’t have to be square or symmetrical, and they allow two-letter words. Notably, they number their grids using a chess-style grid system instead of number “Across” and “Down” lists.

If you want to mix things up, try checking out mots fléchés. Mots fléchés, or arrowwords, are arguably preferred to crossword puzzles in Europe. They are effectively still crossword puzzles, with a more accessible twist. Mots fléchés are typically considered to be easier than crossword puzzles, a sort of “gateway puzzle” if you will. Originating in Sweden, mots fléchés came to France by way of linguist Jacques Capelovici. Mots fléchés take the clues and put them directly into the puzzle, thus integrating the two in one neat grid. You can also try mots mêlés (also known as mots cachés), which are classic, tried and true word searches.

Word games and puzzles are a great way to increase your phonotactic awareness in your target language. Put simply, phonotactics are a language’s specific rules that govern where sounds, or phonemes, can be placed in a word or sentence. For example, English words cannot begin in [ŋ] (this is the International Phonetic Alphabet symbol for -ing). Playing word games and puzzles will help you pick out rules like this in French, which in turn will help you in deducing and constructing French words like a native speaker.

Watch Real Frenchies Play

Des chiffres et des lettres, is a French game show that’s a bit like wheel of fortune, except it also includes math. The show is an updated version of the old show Le mot le plus long, which is French for “the longest word.” The first round involves doing exciting things involving basic math. The second round is a bit like Wheel of Fortune-meets-Boggle.

Get Started!

Luckily, there’s no shortage of word games online. Le cruciverbiste has a ton of free mots croisés, mots fléchés, and mots mêlés. If you’re looking for a more modern game, look no further than your phone. The iOS App-Store has oodles of games to play. A notable stand-out is SpellTower Francais, a word game that plays kind of like Boggle-meets-Tetris. It’s a fun way to flex your word-crafting muscles while clearing rows upon rows of letters. All of these word games will force you to put your thinking cap on and while building your vocabulary. Pro-tip: keep a dictionary nearby to look up new words as you play, you’re bound to come across plenty!

Thanks for Reading!

What’s your favorite word game? Be sure to comment below, and share this post with friends.

(Thumbnail photo by Brett Jordan)

"C'est quoi, Dunkin'?" The French Language in New England

In New England, there’s more to French than just the fries.

by Brian Alcamo

When you think of New England, a few things may come to mind: fall foliage, seafood, and Dunkin’ Donuts. You might even think of (Old) England, with its linguistic, architectural, and cultural influences displayed all over the northern tips of the Eastern seaboard.

What you might not think of, though, is France. It turns out that the French language has a long-rooted history in the region (which, to be fair, also exists in England proper). French was originally part of New England way back in 1604, when the New France colony of Acadia (Acadie, en français) stretched into parts of present day Maine. It turns out that French culture in the United States isn’t limited to Louisiana.

The First Wave of Francophones

Almost a million French Canadians came to New England from the mid 19th to mid 20th century to work in the region’s many mills. The New England Historical society states that “Between 1840 and 1930, about 900,000 residents of Quebec moved to the United States. One-third of Quebec moved to New England to neighborhoods called Little Canadas.”

Historically speaking, French was discouraged by local English speakers, and tensions grew along both religious and linguistic lines. New England was historically home to a strong Puritan tradition, and the region’s staunchest Protestants were typically quick to defend the culture. Francophones often declared “Lose your language, lose your faith,” (“Qui perd sa langue, perd sa foi”) and French was upheld in many of the region’s Catholic churches. However, despite religious ties with the region’s Irish, the two groups did not get along.

Years after the industrial revolution’s end, a dip in Francophone activity occurred as many communities left New England and were conscripted to fight in World War II. WWII and its aftermath contributed to a new speed of assimilation of New England francophones. Many families left New England for both the war effort and for new career prospects as industry moved South and West (source). Despite these demographic changes, a francophone identity remained in Maine and other parts of New England. The culture stayed strong enough to even be part of the childhood of Maine’s previous governor, Paul LePage, who grew up speaking French.

A New Wave of Immigration

In recent years, cultural regeneration programs have begun to elevate French and Quebecois culture in New England, especially in Maine. Serendipitously, these programs have aided in the integration of new immigrants hailing from Africa.

These immigrants are typically asylum seekers from Angola and Congo. The state of Maine has been welcoming migrants with open arms, and is certain that the influx of new young adults and children will be a boon for the state’s economy in the long run. Though the rapid population increase has proved to be a challenge, many state officials are excited by the new diversity in the historically very-white state. Besides hundreds of new workers, the integration of these new francophones has led to a hopeful consequence: older Francophones now have a reason to use their language in a public setting.

These older white speakers who immigrated from Canada and younger black speakers who are now immigrating from Francophone African countries are using French to close generational and racial divides. Jessamine Irwin, a French teacher at JP Linguistics and Mainer says that she has “definitely found that French has been key in building bridges between the aging French speakers of Maine and the newly arrived French speaking African community.” While the intricacies of the dialect may change over time, the fact that French has remained and will remain in the region for a long time is a rarity, Jessamine says.

Planning a Trip

With New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine all being neighbors with Quebec, Canada’s semi-autonomous Francophone province, you can bet that frequent trade and travel occur between the two regions, whose histories have been and remain intertwined since European settlers arrived in North America. French can be heard all the time, especially during New England’s busy summer tourist season.

The tourist industry is even beginning to capitalize on the renewed interest in French-speaking culture, with a new initiative called the Franco Route starting up in 2019. The Lewiston Sun Journal reports that it is part of a new form of tourism called “heritage tourism.” The route runs south from the Twin Cities region of Lewiston-Auburn to Woonsocket, Rhode Island. Catherine Picard of Museum L-A has put together a two hour tour of the northernmost cities on the route, including sights of old mills and Franco-inspired architecture.

The official Franco Route website says that tourists will “discover the motivations, struggles, dreams and achievements of these newcomers” along with visiting “the museums, churches and genealogy centers that preserve this history, as well as the theaters, restaurants and microbreweries that creatively express that heritage today.” The route is a way to connect with the multicultural past and present of the United States, and is proof that people don’t need to leave the country to experience a certain je ne sais quoi.

Like This Post?

Make sure to share, and comment below what you think about practicing your French up North!

(Thumbnail photo by Mercedes Mehling)

French Tenses: The Recent Past and the Near Future

How to talk about what you just did, and what you’re about to do in French.

by Brian Alcamo

Here’s a situation:

You’ve just finished your first semester (or two) of French, and you’re looking to practice with a native speaker. Since no one can meet in person right now, you schedule a Zoom session. You’ve got your passe compose, imparfait, and futur simple memorized to a T, and things are going well (aka you said “bonjour” with a passable r). Suddenly, you hear a phrase je viens de sortir, which translates literally to “I come from to go out.”

“You viens de what?”

Or, in a different conversation, they say “je vais sortir,” which literally translates to the (more intuitive) “I am going to go out.” But maybe you’re still confused. Even though you’re not allowed to gather in public, you worry that sortir could be an amazing club that you’re missing out on.

“Where is sortir? Can I take the subway there?”

In the first conversation, it turns out that your friend is coming from nowhere, but they just went out. In the second, they are going out soon. Not only are you hurt because you weren’t invited, but you and your lost brain are now way behind in the conversation.

What tense did they just use?

Those two tenses are called the passé récent (recent past) and the futur proche (near future), and they’re both extremely useful in day to day conversation.

Luckily, even if you’re not physically coming from or going anywhere during times of corona, you can still practice conjugating the verbs venir and aller. That’s because French (and other languages, including English) uses the same verbs for movement through space as they do for movement through time.

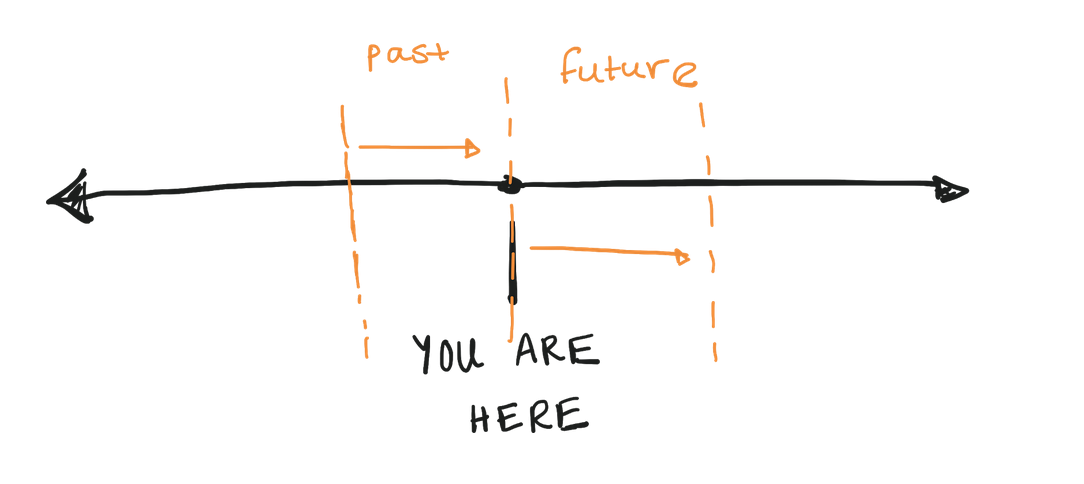

A Refresher on Time

Before we talk about grammar, let’s try to get a grasp on time. No one can get a grasp on time, but let’s try. Pictured below is the present moment:

The recent past and near future (right before, and right after, you have a conversation) are pictured here.

The areas marked off in orange are where we’ll be spending most of our time for this discussion. The orange arrows are to show the forward motion that is inherent in the passé récent and the futur proche. Don’t fret that there are no easy to use verbal constructions for talking about movement back in time. We doubt you’ll need to talk about the process of unbrushing your teeth or ungoing to a party (unless you’re writing a scifi/fantasy movie, in which case, our headshots are ready).

Now that we’ve got time as figured out as possible, let’s talk about tense #1, le passé récent.

Le Passé Récent

The passé récent is formed with venir + the preposition de + a verb in its infinitive form. It’s used to mean that you’ve just done something. Here’s an example:

Je viens de quitter le bureau. “I just left the office”

The French textbook Contraste: Grammaire du Français Courant calls venir a “semi auxiliary,” which is a verb that sometimes behaves like an auxiliary verb. Être and avoir are examples of true auxiliary verbs.

Here’s a refresher on how to conjugate venir in the present tense.

Je viens “I come”

Tu viens “You come”

Il/elle/on vient “He, she, we come”

Nous venons “We come”

Vous venez “You (pl) come”

Ils, elles viennent “They come”

If you’re telling a story and using the past tense, you would simply conjugate venir in the imperfect, saying something like:

Il venait de quitter le bureau or “He had just left the office.”

If you’re having trouble wrapping your head around it, think about it as if you’re walking on a timeline. You’re “coming from” the activity that you just did right before the present moment.

Now that we’ve come into the present from the past, let’s continue into the future with the futur proche.

Futur Proche

In the futur proche, you use the verb aller which means "to go.” You conjugate aller and tack on an infinitive. In this construction, aller functions as a semi-auxiliary verb, just like venir in the passé récent.

So "Je vais danser ce soir," means "l'm going to dance tonight." (Sounds fun!)

In case you need it, here’s a quick repeat of how to conjugate aller in the present tense:

Je vais “I go”

Tu vas “You go”

Il, elle, on va “He, she, we go”

Nous allons “We go”

Vous allez “You (pl) go”

Ils, elles vont “They go”

The future proche is a bit more flexible than the passé récent, because you can say that you're going to do something pretty far into the future. "Je vais aller à Lyon dans six mois" ("l'm going to go to Lyon in 6 months") is a perfectly acceptable sentence. This is because the futur proche can also convey a meaning of intention. With regards to its cousin the futur simple, things stated in the futur proche are usually thought of as more certain to happen.

There are a few other phrases that can be used to convey a similar meaning to aller + infinitive:

être près de + infinitive - “to be close to”

être sur le point de + infinitive - “to be on the verge of”

s’apprêter à + infinitive - “to be about to”

avoir l’intention de + infinitive - “to mean to”

If you're telling a story and using the past tense, you can conjugate alter in the imperfect and add an infinitive, saying something like:

“Nous allions sortir en boite, mais il a commencé à pleuvoir”

“We were going to go out to the club, but it started raining.”

In the past tense, this structure conveys a sense of planning that gets interrupted. Notice that even though you’re using aller to talk about this plan, you’re conjugating it using the imperfect tense, and throwing that futur straight into the past.

Devoir + infinitive when used in the past tense has a similar meaning to the futur proche in the past tense. The meaning here is “was supposed to” or “must have.”

Getting a grasp on time is tough, and the current environment of social distancing has left many people struggling with how to keep track of it. The passé récent and futur proche are wonderful examples of how our brains use the same structure for movement through time as they do for movement through space. And as with a lot of movements, the only way “out” is “through.”

Merci !

We hoped you enjoyed this blog post. Be sure to “heart” it, and to share with your friends. Keep the conversation going in the comments.

Want to review what you learned? Take our quiz down below!

(Thumbnail Photo by Djim Loic )

Barreling Across The Atlantic

And you thought Niagara Falls was the it-place for aquatic barrel rides.

Some people enjoy the slower pace of boat travel compared to air travel. However, one French man in particular has decided to take a very primitive approach to cross the Atlantic.

Photo: Facebook - Jean-Jacques Savin

Jean-Jacques Savin set sail from the Canary Islands this past December in what appears to be something straight out of a cartoon - a barrel made of resin-coated plywood. The measurements worked out to 10 feet long and 6.8 feet across.

The 71 year old spent the first 4 months of 2019 inside his barrel, traveling at about 2 mph as he relied entirely on the ocean current to guide his journey with a bit of assistance from JCOMMOPS, an international marine observatory, which provided him with markers to drop off at various parts of the sea to help study ocean currents.

His epic voyage lasted 128 days, and he posted updates via social media to keep interested viewers in the loop about his adventures. He also was sure to bring treats for the various holidays he would miss celebrating on land including a bottle of Sauternes white wine and a block of foie gras for New Year's Eve.

As far as his return track to France? As one may think, he has opted for a simple plane ride to his homeland.

We hope you’ve enjoyed learning how one Frenchman had the adventure of a lifetime Barreling Across The Atlantic! Would you be willing to take on a journey like the one Savin completed? Join the conversation below!

5 Reasons to Learn a Foreign Language

When attention spans have been reduced to 6 seconds, it's important to find ways to get your brain back on track.

5 Reasons to Learn a Foreign Language

You have probably heard that learning a foreign language is good for you. It is great for your brain, for your job and for your personal well-being, period. There are plenty of great reasons why people choose to learn foreign languages and this post provides a deeper response into what motivates and fuels people to start. We hope you enjoy this unique post and don't forget to share your thoughts in the comments section below!

1. "I Want to Make Better Financial Decisions"

Learning a foreign language allows you to get a broader understanding of a problem and therefore have a more comprehensive vision of how to solve that problem. A study by psychologists at the University of Chicago have found that people who speak a foreign language (especially those fluent in it) eliminate the tendency to get caught up in the 'here and now.' Thus, the study shows that monolingual people (people who only speak one language) are more likely to refrain from investments or financial decisions which they would benefit from down the road. This means that learning foreign languages helps you sift through the 'noise' and make smarter, more long-term financial decisions.

2. "I want to understand my partner"

Many students come to our classrooms with the goal of understanding their (foreign) spouse or partner. It is a goal we hear often and, in our opinions, one of the most rewarding goals when you start actually seeing the results from learning a foreign language. People from different linguistic backgrounds think differently. For example, American English is very inclined to be extremely positive with phrases such as "it is beautiful out!" or "you did such a great job today!" Whereas French, for example, uses negative sentence structures to express a positive thing like "il fait pas chaud dehors" (it is not hot outside = it is cold), or the very common "pas mal" (not bad = good). These examples show how two cultures might express the exact same sentiment, but in two opposite ways. In this case, love is the motivation for many who continue to learn a foreign language and who want to better understand their (foreign) partners. This passion for a foreign concepts is like a "sublime hunger" (as described by Emmanuel Levinas) and it must be fed!

3. "i want Improve MY memory and attention Span!"

In a society where the attention span has been reduced to 6 seconds (yes, 6 seconds) it is important to find ways to get back on track and improve your brain's activity. Surprise! Learning a foreign language will help you accomplish just that. A study conducted by Northwestern University showed that knowing multiple languages forces your brain to pay attention to relevant sounds, while blocking out irrelevant sounds. This makes a lot of sense since you need to adjust the frequency of your hearing in order to "receive" and "decrypt" the message. The study provided the first biological evidence that being bilingual improves your hearing and helps with attention span and working memory. Many adults find it hard to learn a foreign language and believe in the myth that it is too late for them because of age. This is NOT true. You can learn and become highly proficient in a foreign language. There are certain obstacles for adults that do not necessarily exist in children, but they are mainly phonetic. You can do it and your brain will thank you!

4. "I want to Increase my sense of self worth"

There is nothing wrong with being proud of mastering something in a foreign language. Being able to order a full meal while being understood in a foreign country feels great! Let's be honest, we love the feeling of pride and joy that comes with asking a taxi driver to go to our hotel (in a foreign language) and we actually get there! Communication is key and it feels amazing when it works. On a different level, speaking a foreign language contributes to the development of your own personality. It can help you discover a part of yourself you did not know. It can help create a part of yourself that you really want to have. Think of languages as a blank state. You are in charge of building the personality you want. So think of it that way. What persona will you create?

5. "I want To Increase MY NetworkING Skills"

Speaking another language opens up a whole new world of communication and networking possibilities for you! In a world that is becoming more and more connected between Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat and more, it is extremely beneficial to be able to communicate with as many of its members as possible. The technology to do so is no longer a barrier, and once you break down the language barrier, your network can grow tremendously. You can use your foreign language skills to your advantage by quickly jumping to the tweet that others might not be able to respond to. Nowadays, it's about having the skills and the speed.

We hope you enjoyed these 5 Reasons to Learn a Foreign Language. If you are looking to build your foreign language skills, don't forget to check out our Group Classes, and Cultural Events at JP Linguistics. Also, don't forget to share this post with your friends using the simple 'share' button below. Merci beaucoup! Grazie mille! Muchas gracias!

4 Popular French Fragrances and their Origins

Learn about the roots of these four French showers perfumes!

It may seem like common "scents," but many people are not aware of the origins of these 4 popular French fragrances: Chanel No. 5, Sauvage by Dior, Prada Eau de Perfume and Parisienne. Whether you have heard of them, know a friend or family member who wears one, or if you are guilty of wearing one yourself; these perfumes are simply classics, and originated in the backyard of the French countryside.

Nestled into the hills along the French Riviera lies Grasse, France--the perfume capital of the world. Due to the town’s micro-climate and geography, flower farming has been a great success for centuries, producing lavender and other flowers known for their wonderful scents. This naturally led to the eventual success of the perfuming industry after the discovery of organic synthesis (the process of turning scents into fragrances) in the 18th century. Les Nez, or "noses," from all around the world have curbed their senses in Grasse to distinguish between over 2,000 kinds of scents, or simply to tour the perfumeries for a "scents" of the town’s history.

To this day, Grasse produces over 2/3 of all of France’s natural aromas. The majority of French fragrances found their origins in Grasse, including the notorious Chanel No. 5, and other perfumes listed below:

Chanel No. 5

All hail the Chanel gods— Chanel No. 5 is considered the classic fragrance for women. From references of the perfume in pop culture, and the iconic Marilyn Monroe being notorious for flaunting it, a girl can’t go wrong wearing this on a night around town. The now and forever fragrance. The ultimate in femininity. An elegant, luxurious spray closest in strength and character to the parfum form.

This fragrance can be purchased here!

Sauvage – Dior

Dior is another brand known for its timeless scents that transcend each generations. Dior fragrances have been produced in Grasse since the perfume's conception. This particular model, Sauvage, is a radically fresh composition that is raw and noble all at once. Natural ingredients prevail as radiant top notes burst with the juicy freshness of Reggio di Calabria bergamot.

This fragrance can be purchase here!

Prada Eau de Parfum

This oriental amber scent begins with citrus notes of bergamot, orange, bitter orange, mandarin flower, and mimosa. Mid notes of rose, schinus molle, peru balsam, patchouli, and raspberry give way to reveal rich base notes of sandalwood, labdanum, tonka bean, vanilla, amber and musk.

This fragrance can be purchased here!

Parisienne

Inspired by the Parisian female persona, this fragrance is the latest hit fragrance by Yves Sant Laurent. Although the woman it appeals to isn’t native to Paris, she still calls it home. Parisienne is the fragrance of ultra-femininity and sensuality, built with notes of blackberry, damask rose, and sandalwood. The grand floral with a woody structure is luminous even in its mystery.

This fragrance can be purchased here!

I hope you enjoyed these 4 Popular French Fragrances and Their Origins. If you are looking to learn more French language and culture, make sure to sign up for our new Online Classes at JP Linguistics! Don't forget to tell your friends about Frenchie Fridays so they can receive fun French stories delivered directly to their inboxes - they can sign up HERE. Merci et à bientôt!

Photo credit by Patrick Blaise - Pixabay, Wikipedia and Terrance Sterling